A potential new cancer treatment labels tumors with a piece of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, unleashing the patient’s own immune system onto the cancerous cells.

The widespread exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus — whether through vaccination or infection — has primed immune systems to recognize and attack coronavirus proteins. As a result, most people have a ready-made biological defense. In a recent study published in the journal Advanced Material, scientists sought to harness this immune response and redirect it toward cancer.

Tumors are notoriously difficult to treat because they are unchecked growth of a patient’s own cells. The immune system doesn’t recognize them as foreign, and their rapid growth allows them to quickly adapt resistance to chemotherapy treatments.

To evade these issues, cancer scientists have experimented with cancer vaccines, which prime the immune system to recognize and attack tumors. “[A tumor vaccine] does this by introducing specific markers [called antigens] found on tumors so the body can develop a targeted immune response,” explained Zhenglin Yang of University of Electronic Science and Technology of China.

The advantages to this approach are potential long-lasting immunity and, unlike chemotherapy, which also harms healthy cells, the vaccine approach is more precise.

Making tumors visible to the immune system

Unfortunately, tumors don’t stand idly by. “Tumors can evade the immune system by suppressing immune responses or changing their surface markers,” explained Yang. “Additionally, every patient’s tumor is unique, making it difficult to develop a one-size-fits-all vaccine.”

To develop an effective and universal cancer vaccine, Yang, his colleague Xun Sun of Sichuan University, and their team say they needed to bring the tumors out of hiding.

“We aimed to improve how tumor vaccines work by making cancer cells more visible to the immune system,” he said. “Our approach involves getting tumors to display a viral marker that the immune system already recognizes, making it easier to trigger an immune attack.” The viral marker they chose was the SARS-Cov-2 receptor binding domain.

Similar to how the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines instructed cells to present viral antigens for the immune system to remember and attack, the team injected tumors with the genetic instructions to express a protein that the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to gain entry into cells called the receptor binding domain.

“This marks them as ‘infected’ in the eyes of the immune system, triggering a strong immune response,” Yang said. “Since most people have pre-existing immunity to [the receptor binding domain], their immune system can rapidly attack and eliminate these modified tumor cells.”

Promising initial results

The team found that mice injected with the new cancer vaccine showed significant shrinking of tumors and increased survival rates. “We were pleasantly surprised to see that after just two doses of the vaccine, the tumors started to shrink significantly,” said Yang. “After four doses, some mice had no detectable tumors at all.”

The team is moving forward to test the treatment on different types of cancers and to experiment with different delivery systems.

Currently, the cancer vaccine must be injected directly into tumors to prevent other cells from expressing the same viral marker. This limits the treatment’s use for widespread or deep-seated cancers. Developing delivery systems that can seek out and deliver the treatment to tumors exclusively after injection into the bloodstream would dramatically expand the use cases for this treatment.

However, by relying on previously developed and approved delivery systems, and injecting tumors directly, the current version of the treatment reduces costs.

“Our vaccine requires only a small dose because it is injected locally, directly at the tumor site, which helps reduce costs,” Yang explained. “Additionally, since our approach is broadly applicable, we believe that improvements in manufacturing and distribution can make it more affordable for healthcare systems.”

A key benefit to this approach is the speed that building on existing immunity offers. Both in terms of how quickly the body responds and attacks potentially aggressive cancers but also in terms of developing novel treatments based on the many antigens our immune system already recognizes.

But what about the small percentage of people with no prior exposure to SARS-CoV-2? For these people, the treatment likely won’t work effectively, said Yang. However, he believes many common viral pathogens could potentially be used to label tumors.

“In the future, we could explore alternative antigens that target different pre-existing immune responses in the population, such as influenza virus antigens, hepatitis B virus antigens, and herpes virus antigens.”

Reference: Xun Sun, Zhenglin Yang, et al. A universal therapeutic vaccine leveraging autologous pre-existing immunity to eliminate in situ uniformly engineered heterogeneous tumor cells, Advanced Materials (2025). DOI: 10.1002/adma.202412430

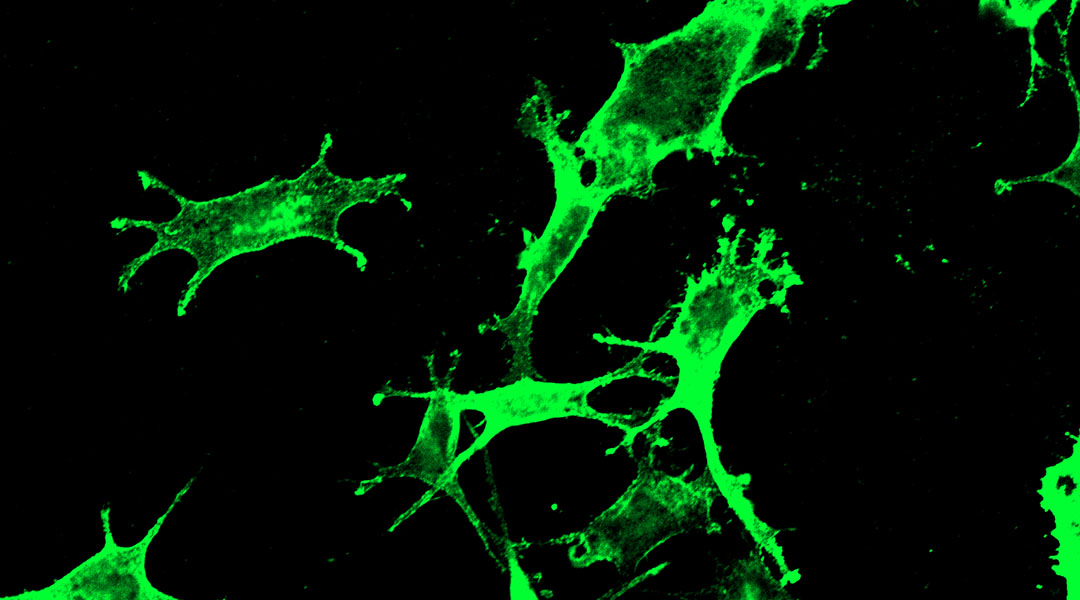

Feature image: Confocal image of B16F10 cells expressing RBD antigen. Credit Xun Sun et al.

This article was corrected on March 5, 2025 in order to properly attribute the quotes to Zhenglin Yang not Xun Sun.