The world of dinosaurs is complex, fascinating, and continually made richer as our knowledge of how these animals lived and interacted with one another grows.

While we cannot go back in time and observe these animals with our own eyes, we have been able to gather enough information to reconstruct a reasonable understanding of their lifestyles and environments, which has helped researchers and artists reconstruct the past. This line of work is called paleoart, and it is one of the primary ways that paleontologists create a living, breathing world from a collection of bones.

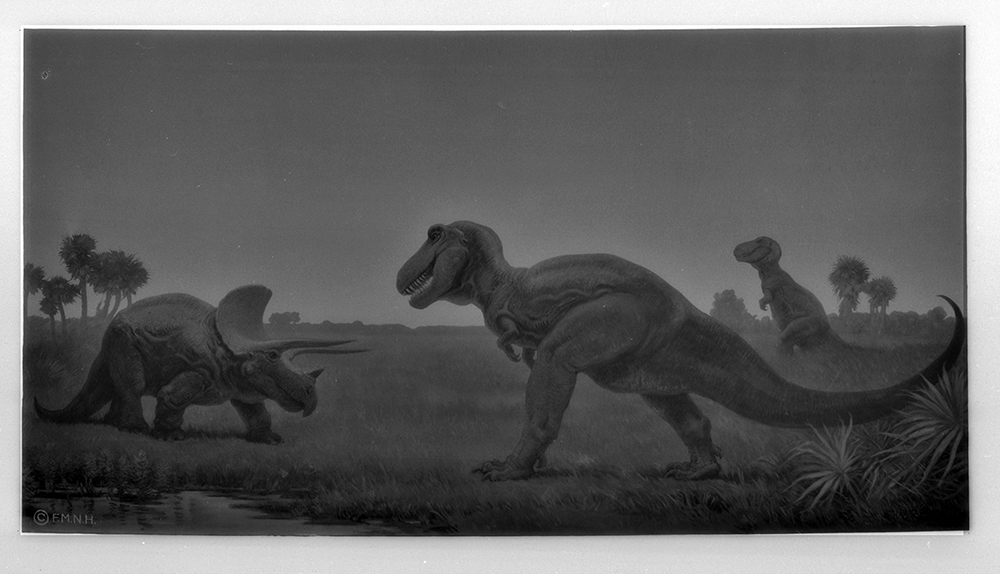

Most artistic renditions of the ancient past feature animals in the midst of battle or in the thrill of the hunt, and it’s not hard to understand why as such scenes are action-packed, attention-grabbing, and overall more engaging for the learner. One notable example of this style of paleoart can be found in Charles R. Knight’s depiction of Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops facing off against one another on the plains of the Cretaceous (see below).

Knight is one of the most famous paleoartists, with his sketch of Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops helping to cement the two beasts as “mortal enemies” in popular culture. He worked during a time when the science of paleontology was not as robust as it is now, and, as a result, much of his work is now believed to be inaccurate.

Nevertheless, he is regarded as one of the great popularizers of the prehistoric past, with much of his work still featured in institutions such as the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Painting a true picture

While the events in images such as these are exciting and adrenaline-fueled, they would have been rare in the context of the daily experience of most animal life. For example, when naturalists observe herbivores in the field, they tend to notice that they spend most of their time doing mundane activities, such as grazing or browsing, while predators spend most of their time resting.

By extrapolating modern animal behavior to the past, we can paint a much different picture relative to what has been depicted by artists, such as Knight. In fact, recent fossil excavations of the herbivorous dinosaur Pachyrhinosaurus suggest little evidence of disease and damage to the bones, indicating an even calmer lifestyle than many modern herbivores.

“Most of the time, if you’re lucky enough to find an animal behaving naturally, it’s going to be rather peaceful, it’s going to be calm,” explained Adam Hartstone-Rose, professor of Biological Sciences at North Carolina State University. “Almost never will you get the opportunity to see animals fighting.”

“When you look at documentaries like Walking with Dinosaurs, they’re always showing a carnivore attacking an herbivore, an herbivore stabbing a carnivore to death, or an animal getting dramatically washed down a river,” he added. “I’ve created many graphic representations of animals, and I always try to create my figures in order to represent the animal somewhat peacefully.”

Hartstone-Rose regularly works on paleoart and is a pioneer in the field. His lab at North Carolina State University focuses on the relationship between anatomical form and behavioral function, a very relevant area of expertise when it comes to transforming fossils into living animals. His philosophy regarding how to approach paleoart stands apart from the traditional portraits drawn by Knight, and sets a new standard for reconstructing ancient ecosystems.

Re-imaging how dinosaurs are depicted in paleoart

His latest work focuses on dinosaurs that lived in the Arctic during the Cretaceous Period, a period of time in Earth’s history that occurred roughly 145-65 million years ago that was alien relative to what exists today. Grasses that modern arctic herbivores rely on had not yet evolved, and the climate was substantially warmer. The landscape was dominated by shrubs, mosses, ferns, and trees, plants that today only thrive in substantially lower latitudes.

Dinosaurs from this time period and location have previously been featured by the television series NOVA on PBS in 2020 as part of a documentary series on arctic dinosaurs. In the show, Nanuqsaurus, a relative of Tyrannosaurus rex, is depicted as a feather covered predator locked in battle with Pachyrhinosaurus, similar to Triceratops, in an arctic wasteland.

Given the latest fossil evidence and knowledge about their environment, however, Hartstone-Rose and his team wanted to re-imagine these animals and their world in a way that is more closely aligned with how they actually lived and behaved. Their work has culminated in a new piece of paleoart featured in the journal, The Anatomical Record, highlighting both Pachyrhinosaurus and Nanuqsaurus under the brilliant light of the aurora borealis:

One important theme in this piece and paleoart in general is to consider conflict and tension, as these dynamics set the tone for the portrait. How are the animals framed and positioned relative to one another? Are they out in the open or at the edge of the forest, about to leave the safety of the trees? How might the animal be thinking and feeling based on the situation it finds itself in?

“The tension here [in reference to his latest work] is a question of whether this might turn into a physical altercation betweenthem or if Pachyrhinosaurus sees Nanuqsaurus already, in which case it just turns and goes away. There are tensions in these natural moments. Animals are almost never fully relaxed, but they’re also almost never in the type of heightened combat that they’re usually depicted in,” said Hartstone-Rose.

Relying on the fossil record

Aside from behavior, the morphology of the animals in frame is also important to get right. When working out what the physical features of animals are and how they can be expressed artistically, paleoartists must look towards the fossil record — the primary tool paleontologists use to help reconstruct important fossils and place geological events in chronological order.

The fossil record is largely incomplete, as many fossils are poorly, if at all, preserved. Though from the fossils we have recovered, paleontologists have been able to create a decent picture of what these animals looked like and even make detailed descriptions of their physical traits.

In the case of Pachyrhinosaurus, fossil specimens are rich and plentiful, giving researchers the ability to paint a clear picture of what the animal looked like. In many cases, however, fossil evidence is severely lacking.

To date, only tooth roots and cranial material have been found for Nanuqsaurus, turning any reconstruction of the animal into a matter of conjecture based on similar fossil material from its close relatives. This is why Nanuqsaurus is only partially shown in the bottom left of the portrait, to make sure that the parts of the animal that are represented are well documented and understood.

Finding complete fossils in many cases is just a matter of luck, depending on several factors, including when and where the animal died and how it was preserved. As a result, our ideas about what these animals looked like will never be 100% accurate, but will continually be refined as we dig up more bones.

While fossil material is enough to give us a basic outline of the animal, it is still hard to discern the finer details, such as whether or not dinosaurs like Nanuqsaurus had feathers or even lips! The presence of feathers among dinosaurs is still a hotly debated topic in the paleontological community as dinosaur relationships are continually being worked out by comparing their skeletal structures with the rest of the animal kingdom, particularly to birds.

As is always the case in science, we are limited by the amount of evidence available to us. However, with modern technology and paleontological research teams working around the globe, our understanding of the past will continue to improve, leading to better art and better science communication about these incredible animals.

Reference: Adam Hartstone-Rose, et al., Illuminating dinosaurs under the aurora borealis—A commentary on the creation of the Arctic cover for Dinosaurs: New Ideas from Old Bones, The Anatomical Record (2023). DOI: 10.1002/ar.25226

Feature image credit: Adam Hasrtstone-Rose et el.