H1N1 influenza virus; Image credit: CDC

The influenza virus, responsible for the common flu, is highly infectious and poses a great threat to vulnerable populations such as the elderly, young children, and the immunocompromised.

Each year, new strains cause seasonal epidemics with rapid transmission occurring in crowded areas including schools and nursing homes, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Current events have brought to light how dangerous and life changing an infectious virus can be. Experts warn that another pandemic, such as the current COVID-19 pandemic — which has caused almost 2 million global deaths at the time of this publication — or the Spanish flu, could easily be caused by a future influenza strain. This is recognized as one of the top threats to global health.

Despite efforts to create a universal and life-long influenza vaccine, this task is still proving to be a major challenge because the virus mutates so quickly. “Annual [flu] vaccines do not always match the circulating strains, and the vaccine coverage is far from ideal,” said Caroline Tapparel, virologist at the University of Geneva. “Therefore, every year there are millions of influenza infections and approximately 650 000 deaths despite the [availability of] vaccines.”

Antiviral agents as a second line of defense

Dr. Valeria Cagno is part of a team of researchers looking to provide a better form of treatment for infected individuals. “Naturally, the second line of defense after vaccines, are antiviral drugs,” said the team in their study.

A number of antiviral agents are currently approved for clinical treatment of influenza, such as oseltamivir and baloxavir marboxil. However, side effects of these medications have caused concern, and more troubling is their loss of efficacy as many of the newer viral strains have become resistant to these drugs.

In their paper recently published in the journal Advanced Science, the researchers sought to develop an effective, non-toxic antiviral drug that could target human and avian influenza viruses.

“An ideal anti‐influenza drug should be broad‐spectrum, by targeting a highly conserved part of the virus and, in order to avoid loss of efficacy due to the dilution in body fluids, have an irreversible effect, that is, be virucidal,” said the authors.

Non-toxic antiviral drug that irreversibly binds viruses

Research into virucidal agents has been extensive, but the team says that no candidate with broad‐spectrum anti‐influenza efficacy has shown convincing post‐infection results comparable to their current study’s findings. “There are many other drugs currently being studied, but they usually target intracellular viral enzymes and they are not endowed with a virucidal mechanism,” said Tapparel.

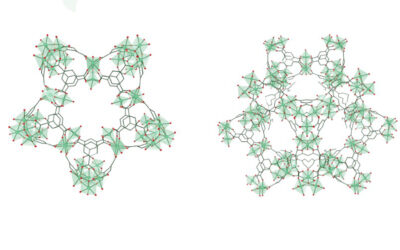

The new antiviral drug is made from a class of macrocycles called cyclodextrins, which are cyclic oligosaccharides that are used widely in medicine to help improve the water solubility and therefore availability of drugs within the body.

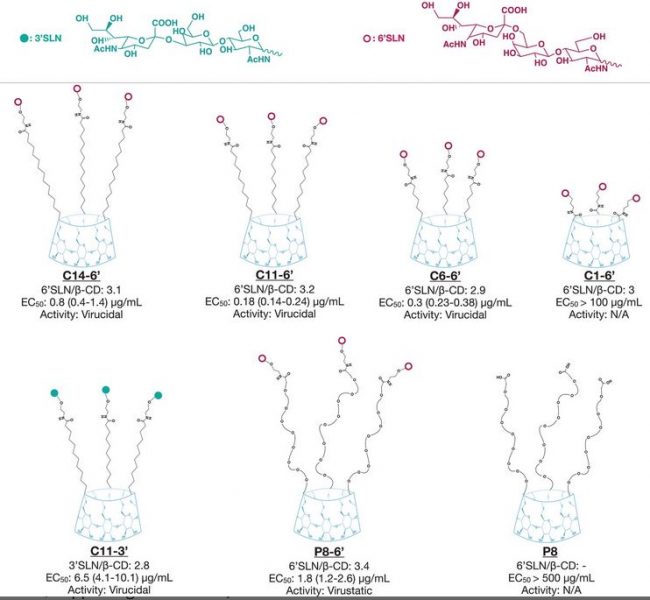

To make their cyclodextrins virucidal, the team attached molecular components that are known to bind to human and avian influenza strains — 6’ sialyl‐N‐acetyllactosamine (6’SLN) and 3’ sialyl‐N‐acetyllactosamine (3’SLN) — using hydrophobic linkers.

While 6’SLN and 3’SLN inhibited viral infection at low doses (in the nanomolar range), the length and hydrophobicity of the linker was found to play a vital role in achieving an irreversible effect, i.e., in attaining virucidal status.

“The macromolecules allow for multi-valency, which is necessary to exert an irreversible antiviral effect,” said Dr Ozgun Kocabiyik, one of the researchers involved in the project. “Our modified cyclodextrins bind to the virus when it is outside the cell using the same sugars that the virus uses to bind to the cell surface. Then, due to their structure, they permanently inactivate it.”

Targeting several strains of influenza

The team was able to show that their macrocycles had excellent efficacy against several human and avian influenza strains, and inhibited recent influenza A (H1N1) and B strains isolated from patients in the University Hospital of Geneva in 2017/18.

“The combination of these two properties allows for efficacy in vitro against several human or avian influenza strains, as well as against a 2009 pandemic influenza strain ex vivo,” said the authors.

In mice, one of the macrocycles containing the 3’SLN group (C11-3′ from the above image) had a 90% survival rate when given 24 h post‐infection, where no survival was observed with placebo or when the commercially available drug oseltamivir was administered.

While the antiviral activity still needs to be evaluated in additional animal models, Prof. Francesco Stellacci, material scientist at EPFL says that the team is working to upscale the synthesis of their modified cyclodextrins, but hope that they could be used in a clinical setting in the next two years.

“We believe that our approach to design non‐toxic virucidal macromolecules has outstanding potential for the prevention and the treatment of not only human, but also avian influenza infections,” concluded the team. With lessons learned from the current pandemic, any arsenal against a similar, future scenario could help us to better prepare and save countless lives.

Reference: Ozgun Kocabiyik, et al., Non‐Toxic Virucidal Macromolecules Show High Efficacy Against Influenza Virus Ex Vivo and In Vivo, Advanced Science (2020). DOI: 10.1002/advs.202001012