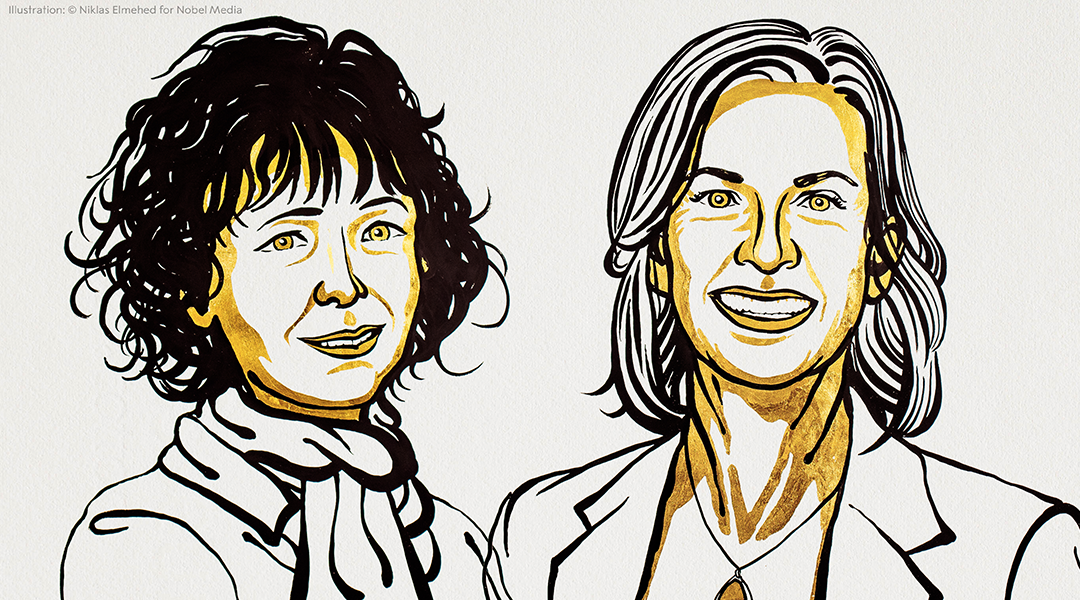

“My wish is that this will provide a positive message to the young girls who would like to follow the path of science, and to show them that women in science can also have an impact through the research that they are performing,” said Emmanuelle Charpentier, one of this years’ two recipients of the Nobel prize for chemistry.

Her remarks go to the heart of one of the biggest strengths of the Nobel prize as an institution; the power of the Nobel brand is such that tonight, news broadcasts around the world will feature a report on Charpentier and Doudna.

Two women will be held up as embodying the peak of an entire field of academic research, and it is hard to imagine a more powerful message to the next generation of students.

Gene Editing

In 2012, Charpentier and Doudna published a paper which significantly improved precision genome editing. They demonstrated the use of a system which allows researchers to make cuts in DNA at specified locations after which the natural mechanics of DNA repair could then be used to paste in a gene of choice.

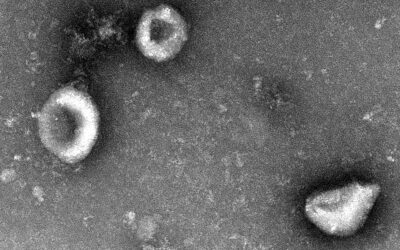

This gene editing system had been used for millions of years by bacteria to help them fight viral infection. First observed in 1987, the painstaking work of a generation of scientists gave rise to an understanding of the system that was so detailed that it could be replicated in the laboratory.

Charpentier dedicated her career to better understanding bacteria and became interested in this particular aspect of their biochemistry. She formed a collaboration with Doudna, after the two met at a conference in 2011, and Doudna’s expertise in the biochemistry helped move the research focus from understanding the mechanisms involved to actively using those mechanisms to edit genomes.

Impact

The commercial implications of the discovery were apparent very quickly. The technology has grown and developed over the decade and is now standard practice in plant research; the rice plant has been edited so that it absorbs less cadmium and arsenic from the soil, and the wheat genome has been edited so that can better cope with drought.

The system demonstrated by Charpentier and Doudna required some modifications to be safely applied to human cells, and research in this field continues today. Nevertheless the technology is currently in clinical trials for blood diseases such as sickle cell anaemia and beta thalassemia, as well as inherited eye diseases.

It has been shown in animal models that this editing technique can be used to treat inherited diseases such as muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy and Huntington’s disease. As the development of the technique goes on, it would not be surprising to see it applied as an experimental therapy in these diseases too.

The development of precision gene editing has had a profound impact on science in the last decade. Charpentier and Doudna are a key part of this story, and it is exciting to see their work recognized today with the 2020 Nobel prize in chemistry.