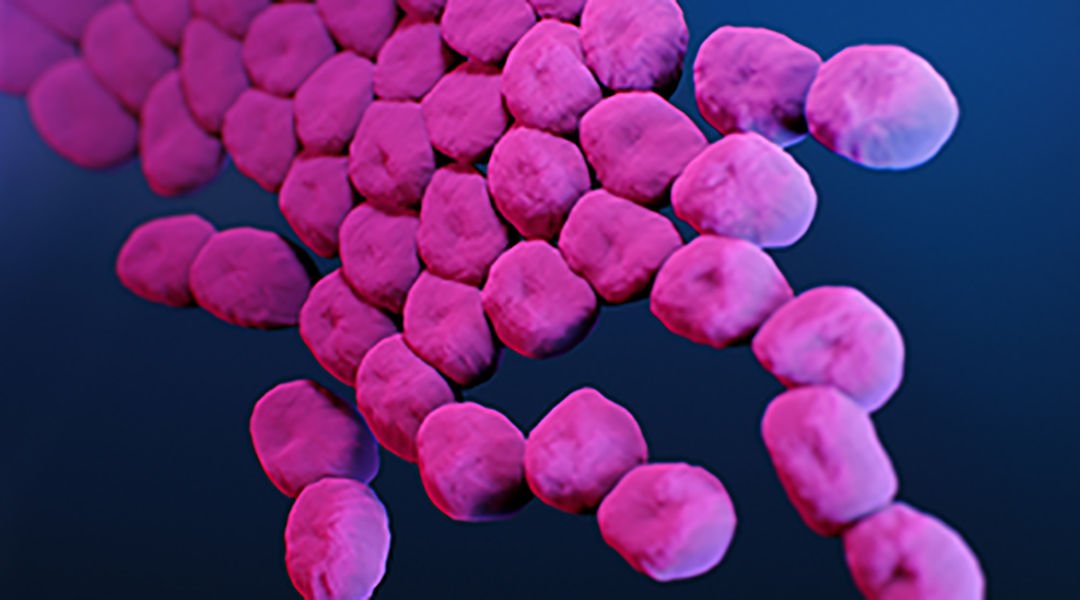

Acinetobacter; Image credit: CDC

A major risk of being hospitalized is catching a bacterial infection. Hospitals, especially areas including intensive care units and surgical wards, are teeming with bacteria, some of which are resistant to antibiotics — they are infamously known as superbugs.

These infections are difficult and expensive to treat, and can often lead to dire consequences for the patient. Now, new research has discovered how to revert antibiotic resistance in one of the most dangerous superbugs, Acinetobacter baumannii, which is responsible for up to 20 per cent of infections in intensive care units. This bacterium can cause a range of infections, including pneumonia, bacteremia, skin and soft tissue infections, and osteomyelitis.

The strategy involves the use of bacteriophages, also known informally as phages, which are harmless viruses that infect bacteria and archaea. “Phages are viruses, but they cannot harm humans,” said lead study author Fernando Gordillo Altamirano from the Monash University School of Biological Sciences. “They only kill bacteria.”

“We have a large panel of phages that are able to kill antibiotic-resistant A. baumannii,” said Jeremy Barr, senior author of the study. “But this superbug is smart, and in the same way it becomes resistant to antibiotics, it also quickly becomes resistant to our phages.”

This resistance to treatment with the phages actually causes the bacteria to lose its antibiotic resistance to commonly used therapeutics. This is because resistant A. baumannii produce a sticky, outer capsule to protect them from antibiotics by stopping their entry. The phages actually use this capsule to enter the bacteria and the researchers leverage this to reintroduce susceptibility to antibiotics.

“In an effort to escape from the phages, A. baumannii stops producing its capsule; and that’s when we can hit it with the antibiotics it used to resist,” said Gordillo Altamirano.

The study showed resensitisation (reversal of antibiotic resistance) of A. baumannii to at least seven different antibiotics. “This greatly expands the resources to treat A. baumannii infections,” Barr said. “We’re making this superbug a lot less scary.”

Even though more research is needed before this therapeutic strategy can be applied in the clinic, the prospects are encouraging.

“The phages had excellent effects in experiments using mice, so we’re excited to keep working on this approach,” said Gordillo Altamirano. “We’re showing that phages and antibiotics can work great as a team.”