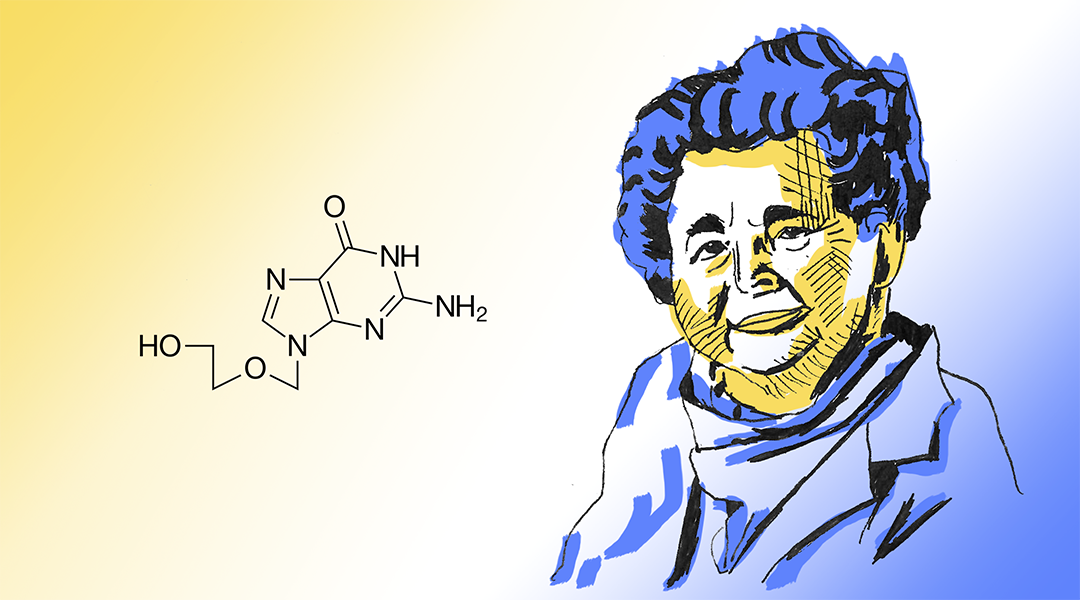

Illustration: Kieran O’Brien

Gertrude Belle Elion was an American pharmacologist and co-winner of the 1988 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her pioneering work in rational drug design.

Born in New York City in 1918, in her Nobel Prize interview, Elion recalls a happy childhood and an early thirst for knowledge. When it came time to choose a specific field of study during her freshman year at college, she is said to have had difficulty deciding, but finally made the decision to become a scientist and study chemistry following her grandfather’s death as a result of cancer.

Due to her excellent grades, Elion was able to attend Hunter College on scholarship, and credits her ability to attend college for free as the reason she was able to pursue a higher education at a time when expectations of young women were still very traditional.

After graduating in 1937 with a degree in chemistry, Elion attempted to apply for financial aid at fifteen different graduate schools. However, she was unsuccessful, which many credit to gender biases that existed at the time. Unable to attend graduate school, Elion sought laboratory work, though during the Great Depression job prospects were poor and even more so for a woman seeking to pursue a career in a male-dominated field.

“I hadn’t been aware that there were doors closed to me until I started knocking on them. …It was a shock … [when I heard] ‘You’re qualified, but we’ve never had a woman in the laboratory before, and we think you’d be a distracting influence.’”1

Working a string of jobs in subsequent years, Elion was able to eventually enroll at New York University for her Master’s degree, where she was the only female student in her class. She continued to support herself by teaching chemistry during the day and carrying out her research at night and on weekends.

After completing her Master’s in 1941, Elion was finally able to get a job in a laboratory, though unfortunately, still not in research. It wasn’t until 1944 that she was offered a position that truly intrigued her. The job was as assistant to George Hitchings at Burroughs Wellcome Company. Here she was able to move beyond just chemistry to the world of microbiology.

At the same time, she also enrolled as a part-time doctoral student at Brooklyn Polytechnic, where she took evening courses. However, she had to make what turned out to be the most critical decision of her life: whether or not to give up her job and register full-time to complete her doctorate. Of course, she ultimately decided to stay and continue her work as a research chemist at Wellcome.

At a time when most conventional drug discovery methods followed a trial-and-error-based strategy, Elion and Hitchings’ application of a new technique termed “rational drug design” marked a radical departure from traditional approaches. Previously, medicinal chemists would synthesize hundreds of compounds related to a molecule that showed promise during a compound screen in order to develop the most effective drug.

Now a common method used throughout the pharmaceutical industry, rational drug design is based on the characterization of a biological target (defining its binding pocket, identifying its natural substrates and their chemical structures, determining physiological function, etc.) and the deliberate design of small molecules to elicit a desired biological response by binding to said target.

The two researchers established this strategy by comparing the different physiologies of healthy human cells with cancer cells, bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens, then using this information to target the reproduction of pathogenic cells while leaving the human host’s normal cells undamaged. This innovative new approach, which was based on an understanding of biochemical and physiological processes, removed a lot of the guess work and wasted time, money, and effort that previously went into developing novel therapeutics.

The two worked closely together over the next four decades, developing an array of new drugs that were effective against leukemia, autoimmune disorders, urinary-tract infections, gout, and malaria.

“When we began to see the results of our efforts in the form of new drugs which filled real medical needs and benefited patients in very visible ways, our feeling of reward was immeasurable.”2

In 1967, Elion was appointed head of the Department of Experimental Therapy following Hitchings’ retirement. She continued with her work in subsequent years, developing acyclovir (Zovirax), an antiviral medication primarily used for the treatment of herpes, and, though Elion officially retired in 1983, helped oversee the development of azidothymidine, the first drug used in the treatment of AIDS.

While serendipity still plays a role identifying new drugs and certain limitations with this process exist, the impact that Elion and Hitchings had on drug discovery is profound. As a result of their distinguished work, Elion, Hitchings, and James Whyte Black received the 1988 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering important principles of drug treatment.

In addition, Elion was awarded a National Medal of Science in 1991, was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame, and is one of the few female recipients of the American Chemical Society’s Garvan Medal (1968).

Though she was unable to officially complete her Ph.D., she received three honorary doctorate degrees from George Washington University, the University of Michigan, and Brown University. While she has stated that she regrets that her parents did not live to see this recognition, she noted in an interview that perhaps that decision (to give up her doctorate) had been the right one after all. Elion passed away on February 21, 1999, and though she in no longer with us, her legacy lives on.

To read about other pioneers in science, you can access our Pioneers Series here.

1 Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles and Momentous Discoveries, 2nd Ed., Joseph Henry Press, Washington D.C., 2001

2Les Prix Nobel. The Nobel Prizes 1988, Editor Tore Frängsmyr, (Nobel Foundation), Stockholm, 1989