Communication with the nervous system has enabled treatment of numerous conditions such as epilepsy and depression, control of prosthetic devices, and the advancement of the field of neuroscience. However, silicon-based neural interfaces are millions of times stiffer than brain tissue. This mechanical mismatch, among other things, results in failure within one year of implantation because of tissue motion around the stiff foreign body and the associated inflammatory response.

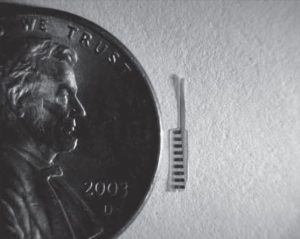

Now, in an attempt to overcome these difficulties, a group of researchers from the University of Texas have developed a processing method for transferring thin-film electronics onto softening polymers, so that they are rigid to allow insertion and 1,000 times less stiff during use in the body. These devices more closely match the properties of brain tissue, are made using standard semiconductor processing equipment and can record individual action potentials from firing neurons. Softening neural interfaces show tremendous potential for long-lasting neural implants for interfacing the body’s nervous system with computers.