For most animals, reproduction has one basic rule: it takes two to produce offspring. That rule isn’t precisely unbreakable, though — under certain circumstances, some female animals that typically reproduce sexually have demonstrated the ability to reproduce without a male. California condors are a famous recent example.

Scientists have observed examples of “parthenogenesis”, more popularly known as “virgin birth”, surprisingly often in nature. Notably, this ability has been seen in certain pest insects such as the tomato leafminer.

Researchers in the United Kingdom, for example, have observed viable egg production in female “virgin” tomato leafminers, which could present pest-control challenges since leafminers are usually managed with a chemical that disrupts mating. If more than a few female leafminers develop the ability to reproduce parthenogenetically, it could mean pest control efforts will be less effective.

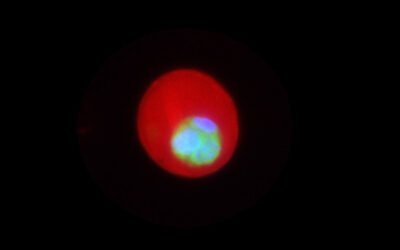

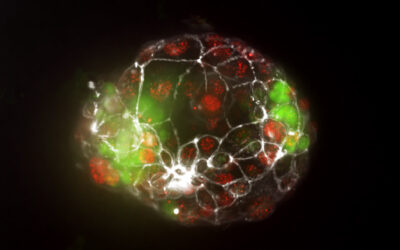

Now, researchers at the University of Cambridge are closer to understanding how parthenogenesis happens in insects. They recently identified the genes that can switch on this ability in Drosophila melanogaster, a species of fruit fly considered a model organism because of its very well-understood genome.

“Drosophila have this cool thing where many flies with different mutations can be purchased from the Bloomington Stock Centre, which makes Drosophila a particularly powerful study system,” said Alexis Sperling, the study’s lead author.

Sperling and her co-authors were able to figure out which genes were responsible for parthenogenesis by sequencing the genomes of two strains of a related fruit fly, Drosophila mercatorum. One strain reproduces sexually, while the other is strictly parthenogenetic.

“We selected a number of candidate genes that were differentially expressed and then, to the best of our ability, tried to replicate the change in expression in the obligately sexually reproducing Drosophila melanogaster. We found a combination that worked!” said Sperling.

Some flies in the second generation were also able to reproduce parthenogenetically, though only 1% to 2% of them demonstrated this ability. And even the flies that could reproduce parthenogenetically still preferred to do it the old-fashioned way: with a male fruit fly.

Is virgin birth possible in mammals?

Parthenogenesis does not occur naturally in mammals, which means our advancing understanding of its genetic origins probably won’t ever make virgin birth practical in animals such as endangered snow leopards or elephants.

“There is a lot of evidence that at least one of the barriers to natural parthenogenesis in mammals is something called genomic imprinting,” said Sperling. Genomic imprinting is a process where certain genes are marked as having come from either the organism’s mother or father. This prevents parthenogenesis from happening naturally.

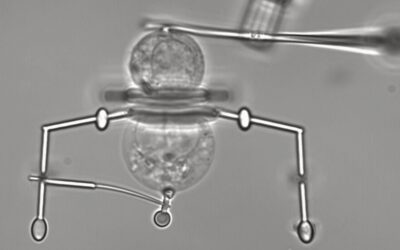

Some researchers have successfully produced live mice from unfertilized eggs, but it isn’t something that could potentially happen outside of a laboratory. “When researchers caused parthenogenesis in mice they could get a limited number of offspring, but this is not a heritable change,” said Sperling. “It requires manipulations that can not be passed from mother to offspring.”

While the idea of inducing virgin birth in a large animal is a little more sensational than virgin birth in fruit flies, parthenogenesis in insects represents a more present concern.

Although the researchers studying parthenogenesis in tomato leafminers concluded that rates of virgin birth were probably too low to cause pest-control challenges, they did also note that a slight increase in virgin birth — along with other population changes — could mean the species is selecting for traits that will make it better at tolerating current management practices. This suggests that understanding parthenogenesis might one day be a critical component of certain insect pest control strategies.

“Very little is known about parthenogenesis in general,” Sperling said. “This current work helps us understand that there is a genetic cause underlying the ability […] at least in flies. It helps to lay a foundation for future research into why this might be becoming a common form of reproduction in crop pests and what human activity might contribute to this change in reproduction.”

“We believe that [parthenogenesis] is much more prevalent than currently documented,” she added.

Reference: A. L. Sperling et al., A genetic basis for facultative parthenogenesis in Drosophila, Current Biology (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.07.006

Feature image credit: Erik Karits on Unsplash