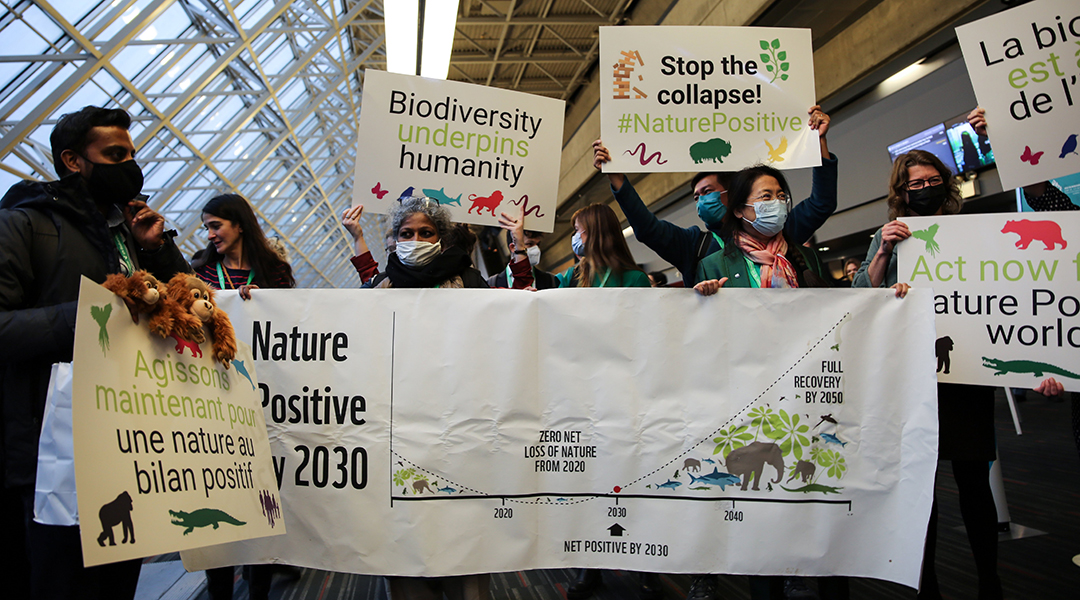

As the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, otherwise known as COP15, gets underway in Montreal, member countries are discussing ways to conserve biodiversity and, at the same time, impose restrictions back home on conservation researchers and data.

An investigation recently published in Science provides the latest example of these restrictions. Foreign researchers were banned from working in Indonesia for publicly contradicting the government’s position that orangutan populations are thriving. The Indonesian Ministry of Forestry and Environmental Affairs further ordered national parks and ministry offices to report any research conducted by foreign nationals and will subject this data to ministerial monitoring and control.

Indonesia is by no means alone, however. In the last decade, the Canadian government was also accused of imposing measures meant to silence scientists. The Trump administration in the US imposed a media black out on and temporarily froze grants from the Environmental Protection Agency. According to Ralf Buckley, the emeritus international chair in eco-tourism research at Griffith University Australia, and Aila Keto, founder and president of the Australian Rainforest Conservation Society, a solution to this problem lies within the COP15 itself.

COP15: A treaty that protects biodiversity research

“This is the international treaty that is supposed to conserve biodiversity. So, if there’s any international legal instrument that could be used to demand freedom of access for research. That’s the one,” said Buckley.

He and Keto penned a letter describing their proposed solution. Simply put, they believe a requirement guaranteeing unimpeded access for researchers to all member countries’ territories should be added to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

One of the goals of the COP15 meeting is to adopt protocols that formalize new agreements in the CBD. However, as Buckly explained, “just putting out some kind of statement, that doesn’t get anywhere there has to be some kind of political power behind that.” For Buckley and Keto, that power is trade sanctions.

The power of international agreements

“We figured if we were going to make this recommendation, we should see how it would play out in real life politics, and whether it was feasible. And our conclusion is yes,” said Buckley. The use of sanctions is regulated by the World Trade Organization (WTO) he explained.

WTO members have essentially agreed not place sanctions on each other. This includes things like import taxes, import quotas, or bans on certain products. “But there is a huge collection of possible exceptions, because you know, the world is complicated,” said Buckley.

Two of these possible exceptions are for environmental reasons, one relating to pollution and the other resource consumption. “But there are all kinds of restrictions on the restrictions,” he explained.

For example, importing countries can’t impose restrictions based on environmental conditions in the exporting country. According to Buckley, “the way the trade, people think, is if they want to damage their environment, that’s their problem, not yours. You can only impose a trade restriction if it’s going to damage your environment.”

But after combing through the language and wording surrounding sanctions and the restrictions on imposing them, Buckley concluded, “there’s nothing that says you can’t impose a sanction relating to environmental research.” Meaning it could be possible for the signatories of the CBD to impose a requirement that all members allow access to conservation and biodiversity researchers, enforceable by trade sanctions and the WTO cannot be used to avoid enforcement.

Using all available means

Buckley acknowledges that this proposal isn’t without challenges and likely won’t be introduced at this session of the congress. “Someone might come back saying, no, no, you’ve misunderstood clause X,” he said of his interpretation of WTO rules. “But a lot of these things operate through political as well as legal means,” he said. Adding that even if the threat of sanctions isn’t imminent, governments may alter their course if they feel the eyes of the world are upon it, “often things work through invisible levers.”

To access all these levers though requires an understanding of the mechanisms available. Buckley’s career spanned academia and industry, giving him the perspective to see how trade rules might be used to further environmental goals.

He believes a lot of good could come from more people having that type of career arc, “there would be a lot to be gained if it were easier for people to make those moves backwards and forwards, you know, to improve the communication between those different components of society.”

Reference: Ralf Buckley, Aila Keto, Combatting national research restrictions, Science (2022). DOI: 10.1126/science.adf400