Image of Adetola Adesida by Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry, University of Alberta

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is one of the most common types of skin cancer, with an estimated 3.6 million diagnoses in the United States annually. As skin sheds, ultraviolet radiation from the sun or other sources can trigger abnormal growth in new cells at the surface, called basal cells. This growth develops into BCC, which will take the form of slightly elevated areas of open sores, red patches, pink growths, or shiny bumps.

While BCC can look different in each person, it is usually located on the face and, more specifically, the nose. Treatment includes surgically removing these growths, which can also include removing some of the surrounding cartilage and replacing it with cartilage from another part of the body. Grafting surgeries for BCC frequently rely on replacement cartilage from the ribs. These procedures are inherently risky due to the proximity to the patient’s lungs and can result in lung collapse or scarring in extreme cases.

“When the surgeons restructure the nose, it is straight. But when [the displaced cartilage] adapts to its new environment, it goes through a period of remodelling where it warps, almost like the curvature of the rib,” said Adetola Adesida, a professor of surgery at the University of Alberta in a statement. “Visually on the face, that’s a problem.

“The other issue is that you’re opening the rib compartment, which protects the lungs, just to restructure the nose. It’s a very vital anatomical location. The patient could have a collapsed lung and has a much higher risk of dying,” he added.

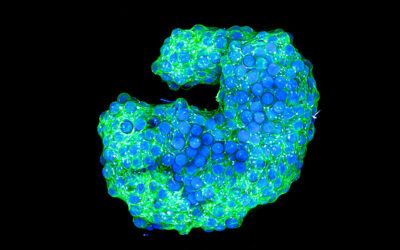

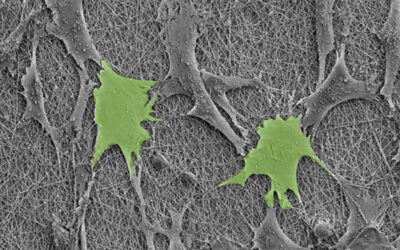

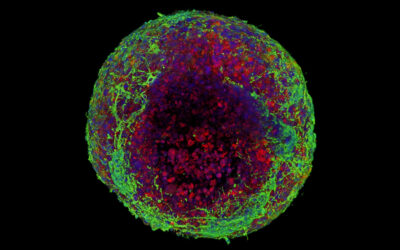

While tricky, a team of researchers from the University of Alberta is trying to make this operation more successful with 3D printing. The team used a hydrogel — a gelatinous, hydrophilic substance resembling Jell-O — mixed with a sample of the patient’s cells.

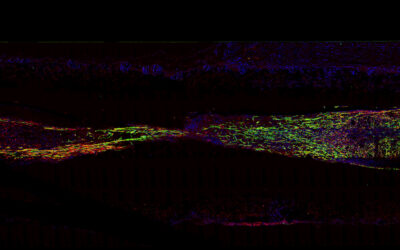

After the BCC tumor is removed, the hydrogel is then 3D printed into a shape that matches the needs of the patient. Over a matter of weeks, the hydrogel is cultured to become functional cartilage that matches the patient’s cells.

“It takes a lifetime to make cartilage in an individual, while this method takes about four weeks. So you still expect that there will be some degree of maturity that it has to go through, especially when implanted in the body. But functionally it’s able to do the things that cartilage does,” said Adesida.

“It has to have certain mechanical properties and it has to have strength. This meets those requirements with a material that (at the outset) is 92 per cent water,” added Yaman Boluk, a professor in the Faculty of Engineering.

Hydrogels lend themselves well to biomedical applications due to its high water content and high versatility. More specifically, the hydrogel matches the strength and mechanical properties of the cartilage it replaces with the added benefit that the potential for the replacement cartilage to fail — called “donor-site morbidity” — is dramatically reduced.

“This is to the benefit of the patient. They can go on the operating table, have a small biopsy taken from their nose in about 30 minutes, and from there we can build different shapes of cartilage specifically for them,” said Adesida. “We can even bank the cells and use them later to build everything needed for the surgery. This is what this technology allows you to do.”

As research on this project moves forward, the team plans on testing the flexibility of the engineered cartilage, as well as further investigating it’s role in cancer surgeries.

Reference: Xiaoyi Lan, et al., Bioprinting of human nasoseptal chondrocytes‐laden collagen hydrogel for cartilage tissue engineering, The FASEB Journal (2021). DOI: 10.1096/fj.202002081R

Quotes adapted from press release provided by the University of Alberta