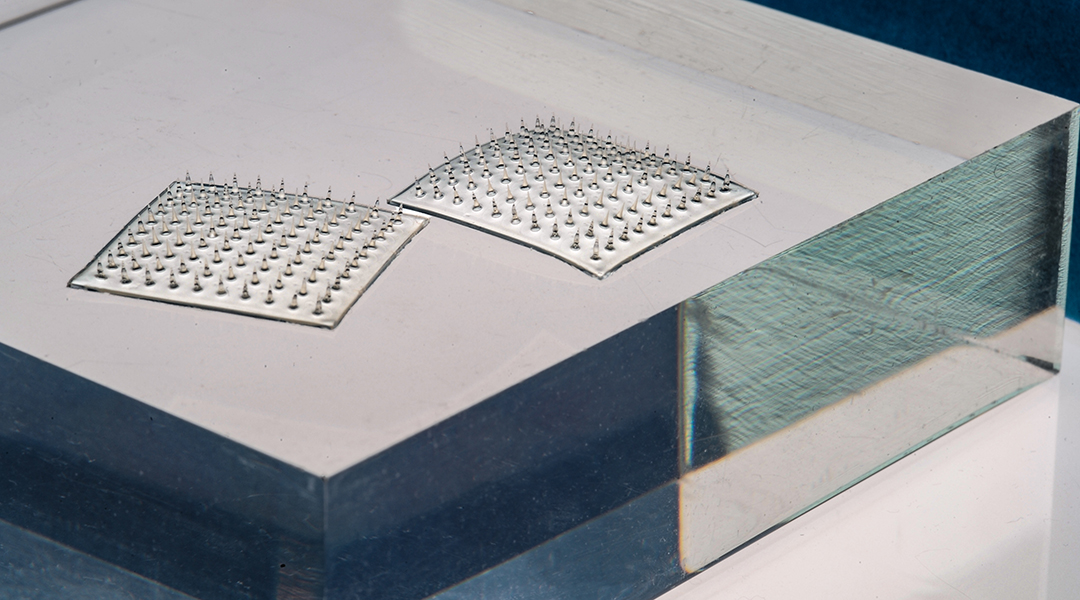

Velcro-like food sensor, made from an array of silk microneedles. Image credit: Felice Frankel

With a growing global population, sustainably enhancing food production is becoming ever-more challenging as land and water resources strain to keep up with demand. One area that could enhance food security is managing food waste, as studies show that approximately one-third of the global food supply chain is wasted annually.

In a recent study published in the journal Advanced Functional Materials, a research team led by Benedetto Marelli, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at MIT, Cambridge, MA, proposes that a major contributor to this waste problem is food spoilage, which poses both an economic as well as ethical burden.

“In the United States, food safety incidents cost $7 billion per year, which comes from notifying consumers, removing food from shelves, and paying damages as a result of lawsuits,” said Marelli. “Additionally, the CDC estimates that each year roughly 1 in 6 Americans (or 48 million people) gets sick, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die of food-borne diseases. In developing countries and in the tropics, damages brought by food spoilage are even more dramatic as it is estimated that almost half of the harvested fruits and vegetables are lost in the food supply chain due to microbial spoilage.”

Cost-effective and easy-to-use methods of detecting food spoilage are critical to addressing this problem. “Currently, food information relies on predetermined expiration dates, which do not inform the real-time food quality and often cause unnecessary disposal of unspoiled food products,” added Marelli. “We aim to solve this problem by developing a safe and cost-effective monitoring platform that delivers food information that consumers can easily recognize.”

Smart food sensors that provide information about the quality of the food have previously been explored, such as chemical reactions that indicate the presence of bacteria or byproducts of their metabolic processes. However, many have seen limited commercial success because they require expensive lab equipment to carry out analysis or are disruptive to the food supply chain, often necessitating opening the package and sacrificing food samples.

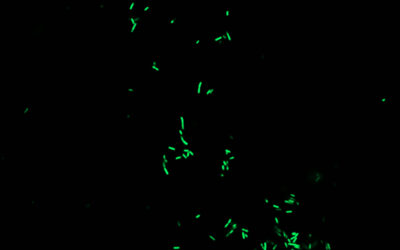

To circumvent these issues, Marelli and his team have developed a silk-based technology that can sample fluids deep in food tissues and render a colorimetric or color change signal to indicate the presence or absence of pathogenic bacteria.

“We developed a microneedle array made of silk extracted from silkworm cocoons, a non-toxic, edible protein,” said Marelli. “The needles can be injected into the food, suck food fluid into their porous structure, and then deliver the fluids to the backside of the array, enhancing the sampling of pathogens, antigens, and toxins.”

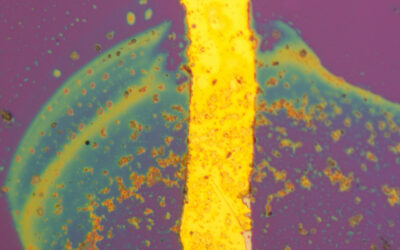

The microneedles act as a safe intermediary between the food and biosensitive inks, which change color in response to the presence of various pathogens; this means that the food never comes in contact with the sensing materials. Compared to surface sensors, the porous needles allow the sensor to penetrate the food’s surface and packaging films, which increases the sensitivity of the sensor by delivering substantial volumes of fluids.

“We want to emphasize that the material used for this platform is food grade, i.e., it has a self-designated GRAS status,” added Marelli. “By leveraging the food-grade materials into a functional device, we provide new insights into the design of food-contact devices.”

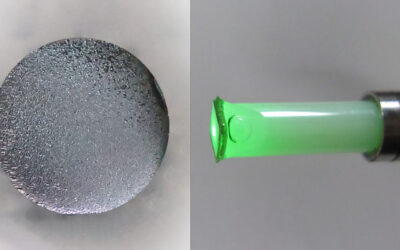

The backside of the sensor contains a printed bioink label made from a polymer called polydiacetylene (PDA) liposome, which has been extensively researched as a colorimetric sensor. Its color changes from blue to red due to a backbone structural change that takes place as a result of environmental changes such as heat, temperature, pH, and mechanical pressure.

The PDA bioink can be tuned to target a specific bacterium by functionalizing it with antibodies for that microorganism, and can also be left unfunctionalized, but will still change color as a result of changing pH, which occurs when food spoils. Multiple pathogen-specific inks can be patterned into the same portable device, creating a smart label that can easily and simultaneously detect a range of pathogens.

The simplicity of the design would allow consumers to intuitively recognize important information with this sensitive label.

According to the team, future studies will involve improving sensing speed by optimizing the porous microneedle structure or modifying the surface properties of the material. “Detecting by-products of pathogen metabolism instead of detecting pathogens directly will significantly improve the sensing speed,” said Dr. Doyoon Kim, post-doctoral researcher and one of the study’s authors. “We will also need to evaluate the application of this approach to other types of foods, such as romaine lettuce and other types of pathogens, such as Salmonella.”

Reference: Doyoon Kim, et al., A Microneedle Technology for Sampling and Sensing Bacteria in the Food Supply Chain, Advanced Functional Materials (2020). DOI: 10.1002/adfm.202005370