Flexible displays, stretchable solar cells and bendable electronic circuits seemed like science fiction just a few years ago, but are now a reality thanks to companies and scientists in the realm of organic electronics.

Our interview series on materials scientists turned entrepreneurs continues with Antonio Facchetti, Chief Technology Officer of Polyera, a well-established startup in organic electronics, and Adjunct Professor in Chemistry at Northwestern University.

1) Can you give me a brief pitch about what the main product of your company, Polyera, is and what is its purpose?

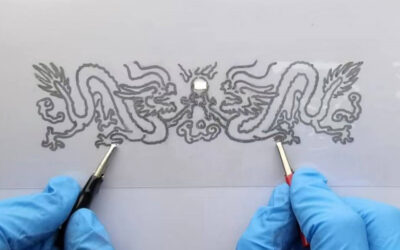

Polyera is a supplier of high-performance electronic materials and inks for organic transistors, photovoltaics, and circuit applications. Our goal is to provide novel functional materials (semiconductors, dielectrics, interfacials, passivation layers) and the corresponding formulated inks to enable the next-generation of solution-processed, flexible, possibly inexpensive opto-electronic devices. Some examples of our products are depicted in the pictures below.

2) What is your role within the company, and how much are you involved now with the business side of the company? How different do you feel that the role you play within Polyera is, with respect to having the same job at a large, established company?

I currently serve as the Chief Technology Officer of Polyera and supervise directly all the chemistry activities at our Skokie facility. I am actually minimally involved in the business aspects of the company since, luckily, we have a great team composed of our CEO, Philippe Inagaki, his assistant General Manager, Brendan Florez and, for our Asian operations, our Senior Vice President, Chung-Chin Hsiao. I never worked for an established, large company but I guess the main difference is that our new technology is all we have, thus, we must make it work or we are out of business. What we do is focus on how we can achieve the goal in the minimum amount of time and at the lowest cost, thus, we must work smart and very hard.

3) When did you figure out that there was a good opportunity for commercial exploitation of this discovery? How long was the process from the “idea” to the creation of the company? Can you give me a detailed breakdown (R&D, IP protection, setting up the company…)?

Polyera started after a group of entrepreneurs, led by our CEO, approached Prof. Tobin Marks and myself. At that time I was working as a Research Assistant Professor at Northwestern University under Prof Marks’ guidance. The investors realized that we had developed (and patented) a unique set of semiconductors. That was the beginning, which took about six months. The company was funded in August 2005 and it took about one year to establish our own laboratory, and to start hiring key people. I joined the company full time in 2008 while maintaining a courtesy appointment as Adjunct Professor of Chemistry at Northwestern University. The company has grown mostly during the last couple of years, from about 10 employees until 2010 to the current 50+ employees.

4) The process of IP protection: what restrictions did it place on what you could and could not talk about with colleagues and at conferences, as well as on your scientific publications?

This has been quite challenging and I had to learn how to balance dissemination of scientific concepts with the Company needs. During my career I have published about 270 papers in peer reviewed journals, and probably about 50 of them with the Polyera affiliation. Thus, I think I can disclose interesting results without compromising our core technologies. Obviously, I cannot disclose the chemical structure of our best channel semiconductors or polymers for solar cells; however, thanks to great collaborators, I can use “old” generation materials which in any case have very interesting properties. This allows my team and I to publish under certain circumstances.

5) Did you participate in the funding roundups?

I am typically involved in the first part of the process, where investors want to learn more about our technology, its challenges and opportunities. After that, I do not have to worry!

6) Before starting this venture, did you want to become an entrepreneur?

No, it was not my plan, but three people enabled this to happen. When I was studying Chemistry and working 6 nights/week in a restaurant –I am a good cook– I dreamed of becoming a Professor in Italy. I was lucky to have the greatest PhD advisor I could find, Prof. Giorgio Pagani at the University of Milan. He taught me heterocyclic chemistry but, most importantly, the love for science, curiosity as a tool for discovery, and how to work hard and efficiently. Knowing the difficult situation of academia in Italy, he pressed me to go abroad. “You must go to the US and learn, then you can come back”. I never returned but his lessons have always been with me, also when I decided to join Polyera. The second person is Prof. Marks, an amazing scientist, incredibly hard working, but also an excellent communicator and writer. The third is Phil, our CEO, who is the real entrepreneur. He convinced me to join Polyera, created the conditions to make it happen, and made me understand the incredible feeling to have your discovery in a commercial product.

7) How influential was the environment you were in? Are many startups created around Northwestern University? Were there any key facilities/procedures/initiatives at your university that substantially simplified the process of creating a company?

Northwestern is a great place to be for three reasons. First, Prof. Marks and his group are exceptionally creative and multidisciplinary. Second, most of the Faculty collaborates very efficiently, which promotes ideas and data exchange. Third, the former TTP (Technology Transfer Program) office and current INVO (Innovation and New Ventures Office) office, which handles IP and technology transfer is really supportive, and there are really good people working there. The combination of these factors enabled the start of several companies in the last few years, spanning fields as diverse as optics, nanotechnology, biology, and electronics.

8) What is the main change in mindset that this venture brought to you? What is the most important thing you could not have possibly understood had you not participated in the founding of this company?

8) What is the main change in mindset that this venture brought to you? What is the most important thing you could not have possibly understood had you not participated in the founding of this company?

Well, the most important change is the goal. I must organize the R&D on the basis of project priorities and customer needs. What I understood the most, and maybe the best word is appreciated, is the complexity of the path from discovery to making a product: the engineering aspect of it is fascinating.

9) What advice would you give to someone with a good idea who wants to commercialize it? Or, what would you have done differently?

With extremely few exceptions or serendipitous discoveries, no ideas, as great as they could be, are ready for commercialization. Nowadays, this transition requires a whole team and not only of scientists; you must have a great business plan, a clear business model, and proper customer support. You need help from people not doing research. Thus, I strongly recommend making sure that those people running the business are really committed. Regarding doing things differently, yes, I would have hired scientists with different backgrounds and experience earlier.

10) How has this changed your interaction with other scientists? (i.e. giving things away for free)

Not that much. I have several great collaborators, for which I am grateful. They understand the difficulties of sharing information and none have crossed the line. I am also very careful to supply materials for which there is a possibility to publish, or build upon the results, although the chemical structure cannot be revealed. I can still supply some materials for free if that study can benefit both the opto-electronic community and Polyera.

11) How important do you think being an entrepreneur is in today’s academic world? Do you think departments are more likely to “like” a candidate if s/he has an entrepreneurial background?

I have mixed feelings. On one hand I do admire (full-time) faculty members starting companies and learning from this experience. That should help figuring out how to run a large research group, and it would bring in industry knowledge to the students. However, the mission of academia is to forge a new generation of bright people changing the world. In my opinion the best professor is someone having deep understanding of a given subject combined with (or pretending to have) a sort of naive, idealistic vision of where that research may be applied. Equally important, a professor should teach and inspire a student, not set deadlines, specifications, and quality control protocols.

12) In times of funding crunch for research, do you think this experience gives you an edge?

In general, I do not think so. There are proposals which deal with very fundamental science. Here you need great ideas, how to solve a fundamental problem or discover something completely new. Others are very applied, and here I could have a bit of an advantage.

13) Why did you decide to remain also an academic scientist, as opposed to dedicate yourself full-time to Polyera?

I am actually full-time at Polyera and my appointment at Northwestern is currently a few hours per week. I continue doing it, in part because of the very good relationship between Polyera and Northwestern University, and in part because it is really instructive to work closely with Prof. Marks. Furthermore, Polyera sponsors some research activities at the university and I help supervising these activities besides other projects within Tobin Marks’ group. Also, I believe that both groups benefit from this tight interaction with students coming to Polyera to learn some processes or using instrumentation useful to their own projects and our employees learning from useful discussions.

14) How do you juggle your time between your academic career and your company?

Since I do not run fast, my days are very long. I spend most of my time at Polyera, however I always try to be available for students and post-docs and meetings (often on Saturdays), or when needed. E-mail certainly helps, I could have not done without it. I do recognize that sometimes I would have liked to spend more time at Northwestern, however, now they know my routine and we found a good way to organize the research.

15) You mentioned that Polyera has a subsidiary in Taiwan: how is the work distributed between the different operations and how difficult is it to coordinate the work among different labs in different timezones?

In our Skokie (Editor’s note: a town in Illinois near Northwestern University) facility we carry out all the development of new materials (from chemical design to ~1 Kg synthesis scale), formulation, and first performance evaluation in small area glass or plastic substrates. On the other hand, in Hsinchu we do formulation fine-tuning for large area deposition, device prototype fabrication, and customer support. The coordination between the two sites is really good because we established certain procedures which include scientist exchanges between the two facilities and regular divisional meetings. The meetings occur typically early in the morning and late in the evening, so we must be flexible. But, this is part of being in a start-up.

16) Do you still feel it is important for scientists at a startup company to publish in the open scientific literature, and why?

Yes, if it makes sense from the company’s perspective. As a small company we cannot afford to purchase very expensive tools or rent time on them, much as we cannot afford to carry out experiments with very low chances of success. It is here that great collaborators can play a role. They are interested in working on exciting materials and publishing, the company is interested in the results of detailed characterization or frontier experiments. Furthermore, publications can promote the image of the company in several fields, advertise certain materials, and excite employees working closely to research and development. Thus, I think it is a win-win situation.