Within our body we have approximately the same quantity of our own and external cells. Those foreign cells are microbes that constitute the microbiota: a mix of bacteria, fungi and other microorganisms that live in different organs in equilibrium with our cells, and many of them play important roles in keeping the balance between health and disease.

“Studies by us and others have linked the microbiome development to health outcomes, including allergies, obesity and inflammatory disease (e.g. diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease),” wrote Wouter de Steenhuijsen Piters, a physician and data scientist at the University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands. “It is therefore important to study how the microbiome develops and what factors impact development.”

When a baby is inside the mother’s womb, it is considered sterile, since it does not have any microbiota. The first microbe “seeding” occurs during birth. When delivered by vaginal birth the baby gets in physical contact with the vaginal canal, and this provides access to microbiota from the mother’s feces that will colonize the baby’s own gut. Many studies have shown that baby gut microbiota is highly affected when born by caesarian section, because of the lack of certain microbes that are transmitted only by vaginal birth, but the effects on the microbiota living in other organs have not been explored in detail.

“Given the central role of the microbiome at different body sites in human physiology (including among others, education of the immune system and protection against pathogens), an important question to answer is: ‘if not before birth, when and how does a baby acquire its microbiome?’,” wrote de Steenhuijsen Piters in an email.

De Steenhuijsen Piters and a team of scientists decided to study if and how other routes of microbiota transmission from mother to child occur during the first month of life. In a study published in Cell Host & Microbe, they showed how different routes of microbiome transmission, such as breastfeeding and skin contact, are able to compensate, in cases such as when delivery occurs by caesarian section.

What happens to a baby’s microbiota when born via a caesarian?

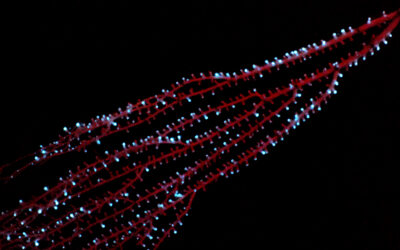

The microbiota does not live only in the gut, but it also inhabits other organs, like the skin, airways, saliva, and more, and it is believed that each and all of the niches play important roles in maintaining the health of an individual. De Steenhuijsen Piters and the team studied six different routes of transmission: feces, skin, nasopharyngeal (airways), breastmilk, saliva and vagina from the mother; to feces, skin, nasopharyngeal and saliva in the baby. This way, they could analyze how different microbiome niches from the mother impact the baby’s microbiota development.

After taking samples from mother and babies over a one-month period, and analyzing their composition, the team found that “Baby microbiomes are impacted by multiple maternal microbiomes, which in total contribute 60% of the infant microbiome composition,” wrote de Steenhuijsen Piters. Importantly, those numbers were also similar for those babies born by caesarian section. “The fact that multiple maternal body sites impact the infant microbiome contributes to the idea that if one of these sources fails to contribute microbes, a child might receive ‘more’ microbes from one of the other sources,” added de Steenhuijsen Piters.

Specifically, the researchers found that when a child is born by caesarian, breastmilk microbiota has a higher contribution to the baby microbiota compared with those vaginally born.

A baby’s microbiota is shaped by many factors

In many cases, the options of vaginal birth or breastfeeding are not a choice, and the study by de Steenhuijsen Piters and his colleagues proves that those are not crucial to the “seeding” of the infant microbiota. For example, the scientists found a higher contribution of the mother’s airway microbiota to the microbe composition in the skin and saliva of the infants when they were exclusively fed with formula, compared with breastfed babies.

“Our data also show how versatile the [microbiota] system is, showing that diminished transmissions through one transmission route, can be compensated by other routes (possibly also in the case of caesarian birth/formula feeding),” said de Steenhuijsen Piters. “[Although] the effects we describe are not black-and-white, as in: a child born by caesarian section and formula fed also develops a functioning gut microbiome by gaining microbes from the mother and other sources. However, microbiome development may be slightly delayed for example,” he added.

Moreover, the microbiota development during the first month of life was also affected by additional factors, like the existence of siblings, hospitalization duration after birth, and the taking of antibiotics by the mother.

While the published study shared the babies’ microbiota state only one month after birth, the team plans to keep tracking its development for a longer time. “We aim to follow our cohort for up to five years to see how early microbiome transmission relates to longer term health outcomes (e.g. asthma/wheezing phenotype and lung function),” wrote de Steenhuijsen Piters. Hopefully, the results they get will help us better understand how microbiota development in early life impacts health outcomes to, in the future, be able to prevent, diagnose, or treat related health problems.

Reference: Debby Bogaert, et al., Mother-infant microbiota transmission and infant microbiota development across multiple body sites, Cell Host & Microbe (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2023.01.018