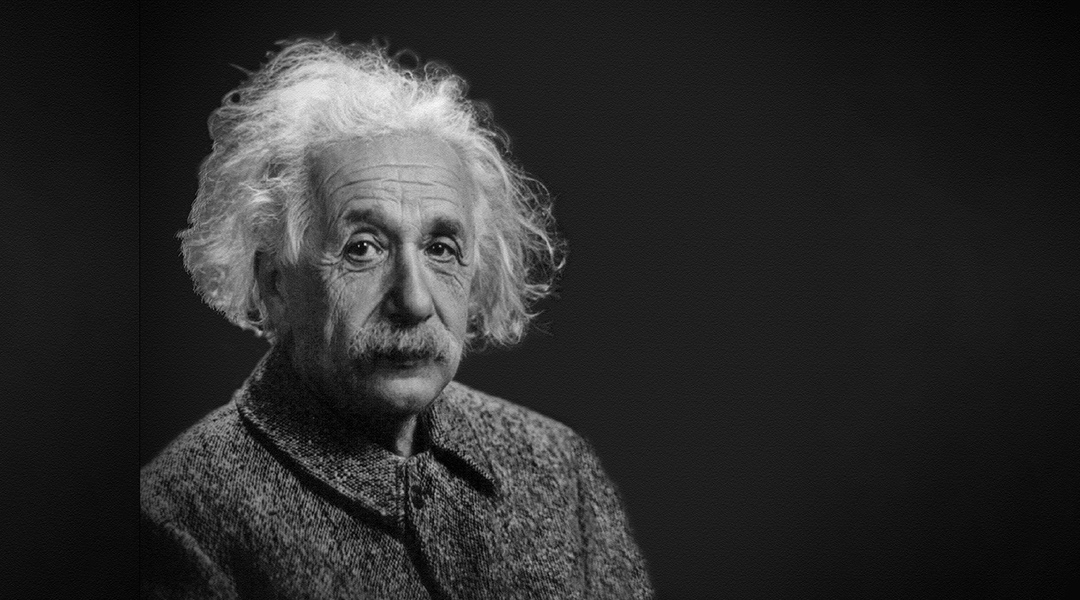

On 9 November 1922, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences voted to award Albert Einstein the previously reserved 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics for “his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect.”

This decision prompted several decades of speculation, especially with respect to the reason for omitting Einstein’s theories of relativity. When changes in the statutes (1974) eventually gave researchers access to official archival materials 50 years and older, historical scholarship could begin challenging conjecture and myth.

Yet, as the 100th-anniversary of this prize approaches, some confusion remains as to what actually transpired and what it means. The Academy of Sciences and related official Nobel sources have long represented this episode along a line that turns out to be incompatible with the historical record. Their version in part draws on physicist Abraham Pais’s account of how Einstein got a Nobel Prize.

Claiming Einstein received a prize for his theory of the photoelectric effect and attributing relativity’s absence simply to an unfortunate error in committee member Allvar Gullstrand’s evaluation, the Academy of Sciences’ narrative represents a misunderstanding and oversimplification of a much more complex and troubling history.

A Swedish prerogative

The Nobel Prize in physics may well be international in scope, but since its beginnings in 1901, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has determined the outcome.

During the first 50 years of proceedings that have been studied in detail, committee members relied largely on their own judgement. No juggling of statistics related to nominations — number, frequency, or origin — explains the awards. Those entitled to nominate rarely provided a clear mandate for any single candidate. Regardless, the committee seldom selected those candidates who enjoyed a consensual or even majority status from the nominators.

The Swedish committee members’ own comprehension of scientific accomplishment, their own priorities as to what was important, and their own group dynamics all proved critical for the outcome. But in order to make sense of the committee reports, and the decisions recorded therein, a deeper understanding is needed of the committee members.

The committee’s well-polished texts represent an after-the-fact justification for its recommendations sent to the Academy of Sciences; the final reports are not repositories of the processes of trying to arrive at a consensus. The act of writing was also an act of erasing the, at times, contentious processes marked by, let’s name it, bias, arrogance, and even pettiness.

1920: Fame, reactionary foes, and a surprise

At a joint meeting of the Royal Society of London and Royal Astronomical Society held on 6 November 1919, the retired Cambridge physicist, J. J. Thomson, announced the results of the now-famous British eclipse expeditions. Notwithstanding a number of inconclusive photographic plates, a sufficient amount of reliable data confirmed the minute bending of starlight by the sun’s mass that Einstein had predicted based on his general theory of relativity.

In Europe, still recovering from the horror of world war and anxious over political and social upheavals in its wake, news of a theory that overthrew the foundations of physics, and glimpses of its highly unconventional creator, attracted media attention. During the first half of 1920, not only did much of the scientific community recognize Einstein for his achievement, but the ever-growing mass media’s attention also helped generate a world-wide fascination with relativity.

Scarcely understood by the general public, relativity nevertheless assumed an unprecedented role as symbol for the new uncertain era emerging from the ruins and upheavals of war and revolution. Political movements on both ends of the political spectrum began to embrace or attack relativity for their causes. Not necessarily to his liking, Einstein was transforming into an international celebrity the likes of which was unprecedented. Not all physicists accepted the British results as valid proof of Einstein’s theory; and not all physicists were intellectually equipped or willing to understand the theory.

Einstein was no stranger to the Nobel committee. He had been nominated as early as 1910; a trickle of nominations turned by 1917 into modest but substantial annual support. Although for 1920 few nominators sent in proposals, Einstein dominated the sparse list. These included nominations from Niels Bohr and several Dutch physicists including laureates, H. A. Lorentz, Heike Kamerlingh-Onnes, and Pieter Zeeman.

No doubt, some eligible nominators did not participate as a protest over a German sweep of science prizes in 1919 — Max Planck, Johannes Stark, and Fritz Haber — seemingly in defiance of the Allied nations’ boycott of German science.

The five-member Nobel Committee for Physics was dominated, as it had been from the start, by Swedish physicists with a strong commitment to an experimentalist creed that largely relegated sophisticated theory and mathematics to an insignificant role in the advance of physics.

In its 1920 general report to the Academy, the committee dismissed Einstein based on [a special report by committee member Svante Arrhenius] on the degree to which Einstein’s predictions based on relativity theory had been confirmed — the bending of starlight passing near the sun, the irregularities in Mercury’s orbit, and a shift toward the red end in the solar spectrum.

Much of his brief seven-page report emphasized the negative claims against relativity, including those from some of Einstein’s most ardent German detractors. Arrhenius completed his report during the first half of August 1920, just when German anti-Einstein agitation was becoming more public and more virulent.

Arrhenius refers to some of the extremist anti-relativity literature in his seven-page special report for the Nobel committee. After briefly noting general relativity’s ability to account for the minute irregularities in Mercury’s perihelion motion that Newtonian mechanics fails to explain, he then devotes over a half page to Ernst Gehrcke’s [previously published] criticism of Einstein on this largely undisputed success for relativity.

According to Gehrcke, this anomaly had already been resolved decades earlier by a little-known German researcher, Paul Gerber. Based on classical aether-physics, Gerber’s achievement meant there was no need to accept Einstein’s revolutionary reformulation of space and time to account for this puzzling phenomenon. When Einstein had earlier refused to respond to these claims, Gehrcke began to accuse Einstein of plagiarism, which in turn, became a common charge by the far-right against him and relativity.

Arrhenius failed however to mention that Max von Laue and other [supporters] had earlier decidedly refuted and repeatedly dismissed Gehrcke’s argument, by having demonstrated serious errors in Gerber’s calculations.

Turning to the British eclipse results, Arrhenius accepted the skeptics’ argument that the margin of experimental error was larger than the effect to be measured. He declared that these results cannot be admitted as evidence as questions remain about their degree of exactness. He then notes that all efforts to identify a redshift in the solar spectrum had failed.

Arrhenius closed his report, dated 17 August 1920, with several references to literature by various anti-Einstein writers. In a highly unusual practice, he cites articles published in newspapers, largely the ultranationalist Deutsche Zeitung. These included contributions from scientifically and politically dubious authors, such as Hermann Fricke and Johannes Riem, the latter an openly antisemitic Christian opponent of what he considered “Jewish materialism.”

Also mentioned are the “fanciful and fanatic publications” of Rudolf Mewes, a reactionary anti-Semite who supported restoring the Kaiser and opposed the alleged conspiracy to replace true German science with Jewish abstract, derivative knowledge. Arrhenius includes a comment that for the upcoming national meeting of German natural scientists at Bad Nauheim in September, preparations were underway for a “neutralizing [oskadliggörande]” of Einstein from “all layers of all the natural-science disciplines.” Toward that goal, both Gehrcke and Lenard, among others, were expected to be the main presenters.

Arrhenius concludes his evaluation with a quotation from Lenard’s recently reprinted polemic against relativity followed by an abrupt ending consisting of Lenard’s assertion that much of Einstein’s theory must be recognized as “untrustworthy [ovederhäftig].”

The report takes little notice of what the nominators and others found valuable in Einstein’s work. While he wrote his report, the full extent of the extremist political and racist background to much of the German anti-Einstein movement may not have been clear. Still, Weyland and Lenard’s letters coupled with the fact that Lenard and Gehrcke had long been highly critical of relativity were clear indicators of the evolving situation in Germany. Moreover, he met officially and privately in June 1920 with Einstein-supporters, Planck and von Laue, as well as with the ultranationalist relativity-opponent Stark, when they all attended the Nobel ceremony.

With his deep concern for German science, it is inconceivable that Arrhenius did not discuss current events with them. He enjoyed especially good relations with both Planck and Stark, the latter had recently arranged an honorary doctorate from Greifswald University in which he emphasized nordic Arrhenius’s role in helping German science and the common racial, religious, cultural, and political heritage of their nations.

It remains puzzling why Arrhenius included this literature in his report and why, when he shortly thereafter must have understood the unsavory political and racial views expressed by many of the major German opponents of relativity, he remained silent. What Arrhenius actually thought of Einstein and relativity is difficult to pin down. His extensive correspondence reveals no particular interest in relativity; he was not a passionate opponent as were several others on the Nobel committee. Still, Arrhenius might well have been surprised and dismayed by Einstein’s response to his letter of sympathy and solidarity sent to many German scientists in the aftermath of defeat in November 1918. Einstein expressed glee over the end of the Kaiser’s Empire and declared himself to be a democrat and republican, who was deeply concerned with issues of human rights. Neither Arrhenius nor his many close relationships in German science were democrats or republicans.

1921: Bias and arrogance

By 1921, Einstein’s status in the physics community was consolidated. As part of this process, he had received comparatively broad international public support from Nobel Prize nominators. Some, such as [the Dutch physicist, H. A.] Lorentz and Planck, portrayed Einstein’s status as being that of a scientific giant, the likes of which has not been seen since Newton. Both theoretical and experimental physicists proposed Einstein for the Nobel, especially for his work on relativity. Some claimed that it would be difficult to consider other candidates without first seeing Einstein recognized. Einstein’s mandate overshadowed all other candidates.

Gullstrand took it upon himself to write a detailed report on Einstein’s relativity and gravitational theories. Gullstrand, a brilliant contributor to physiological and geometric optics, defined himself as both ophthalmologist and physicist. He is largely remembered for his path-breaking instrumental innovations for studying the eye and his complex analyses of the eye as an optical system. He received the 1911 Nobel Prize in medicine.

Gullstrand’s extraordinary talents were accompanied by stubbornness and arrogance. For over 25 years, he refused to admit error after concluding that the retinal macula, responsible for color vision, was devoid of yellow coloring. Similarly, he rejected advice to abandon his personal cumbersome and confusing form of mathematical analysis when more expedient, and more readily comprehensible forms, became available. Like Arrhenius, his command of recent theoretical physics was limited.

Gullstrand’s unusually long, 50-page evaluative report appears at first glance to be comprehensive and to engage with details of Einstein’s work. Closer inspection shows an internal logic based on the premise that Einstein cannot be right.

By 1921, the political and racial aspects of the German anti-Einstein campaign was well known, yet Gullstrand explicitly stated that he accepts the content and conclusion of Arrhenius’ 1920 evaluation. Gullstrand aimed at defusing those aspects of Einstein’s theory that called for “an overhaul of the commonsense foundations of mechanics.”

According to Gullstrand that which remained once Einstein’s errors and unproven assertions were eliminated could best be treated successfully by classical mechanics. He refers to literature written by Einstein’s supporters as being subjective, delivering unsound and insufficiently proven claims from a “cult of believers.” “Belief” rather than evidence-based scientific reasoning recurs several times in Gullstrand’s discussions of those who accept Einstein’s theories. No similar criticisms are directed toward Einstein’s opponents.

Gullstrand does not explicitly refer to Gehrcke’s arguments related to Einstein’s treatment of the Mercury perihelion anomaly; no doubt because he presented his own critique and explanation. The British eclipse data, according to Gullstrand, are useless. Even if the minute bending of starlight actually received confirmation, that would not constitute proof of Einstein’s 4D space-time.

He based that conclusion on a little-known Norwegian-language, semipopular scientific article by meteorologist and aether-physicist Vilhelm Bjerknes. Gullstrand refers extensively to Bjerknes’ effort to account for the deflection using classical physics. In the end, Gullstrand asserts that Einstein’s theories are devoid of any real content and have no relationship with physical reality; they lacked “the significance for physics for which an awarding with a Nobel Prize can come into question.”

The committee accepted Gullstrand’s evaluation and recommended to the Academy that because no candidate was deemed worthy, the prize for 1921 should be reserved until 1922. No member of the Nobel committee accepted the British data as valid evidence

As usual, the minutes of the full Academy’s Nobel meeting record only the result of the vote, and little more. Still, a number of archival sources provide some insight into the event. The Academy’s discussion revealed gaps in Gullstrand’s command of physics and, in an emotional outburst, also his prejudice. Indeed, in spite of devoting almost a year aiming to prove Einstein wrong, his efforts to master the mathematical and theoretical details proved insufficient.

While working on his report, Gullstrand occasionally had discussed his objections to Einstein’s theories with [theoretical physicist Carl Wilhelm] Oseen, who tended to respond very quickly by pointing out Gullstrand’s misunderstandings. Oseen told the younger theoretical physicist, Oskar Klein, about these tribulations while noting that Gullstrand was hindering a prize for Einstein. Oseen confessed to Arnold Sommerfeld that it was a misfortune Gullstrand had to evaluate theoretical work that he did not understand.

A rebellion that year in the Academy against the committee was unlikely. Many if not most members of the Academy were staunchly conservative politically and scientifically. Equally important, the Academy’s culture of deference to authority meant that voting against Gullstrand’s conclusions would constitute a grave insult, especially when he, one of Sweden’s most accomplished scientists, was so adamantly opposed to Einstein.

It mattered little that leading international physicists had praised Einstein as the greatest living representative of their discipline and had declared his accomplishments in relativity theory to be among the most significant in the history of science. Local “expertise” had spoken; the Academy guarded its own authority and its own right to assess and judge.

For 1922, Einstein again dominated the nominations. Bohr also received strong support. Gullstrand supplemented his report. He rejected suggestions of bringing in a foreign expert to assist with the evaluation. Privately he declared that Einstein must never receive a Nobel Prize. He continued to adhere to Gehrcke’s argument that mass suggestion created the popular mania over relativity.

Gullstrand agreed that new discoveries will soon reveal Einstein’s hoax; the enormous interest in relativity will then rapidly “evaporate [fördunsta].” Again, Gullstrand ignored the nominators’ enthusiastic declarations and extraordinary praise. From his perspective, even scientists can succumb to mass suggestion.

As in 1921, Gullstrand declared that Einstein’s theories lack the significance for physics needed to be considered for a Nobel Prize. The committee accepted this judgement without any formal dissent.

1922: Enter a master of strategy

In addition to Einstein’s contributions to relativity and gravitation theory, some nominators had also been praising his many other seminal contributions as warranting a prize. These included his work with quantum theory, especially through his theories of the photoelectric effect and of specific heat of solids; others mentioned his work related to Brownian motion and kinetic theory. In both 1921 and 1922, one lone nominator, Oseen, specified Einstein’s discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect. He chose his words with care.

The law of the photoelectric effect emerged in connection with Einstein’s 1905 paper “On a Heuristic Point of View Concerning the Production and Transformation of Light,” where he suggested that light behaves at times as discrete, individual particles. Few physicists at first accepted Einstein’s claim for a corpuscular nature of light. A number of scientists gradually provided experimental data that tended to confirm the law.

When the committee met early in 1922 to assign reports, it accepted the need for greater expertise in theoretical physics. It petitioned the Academy in May to coopt Oseen for the committee as an ad hoc member. Once on the committee in June, he insisted on maintaining a clear demarcation between his own nomination of the discovery of the law and those that specified the theory of the photoelectric effect. Oseen wanted Einstein to receive a prize, but not for relativity; equally significant, he strongly supported awarding a prize to Bohr.

Oseen had long supported Bohr’s professional development and admired his quantum theory of the atom and its unexpected successes as something of great beauty. The Nobel committee had been dismissing Bohr’s candidacy on the basis that his quantum theory of the atom was in conflict with physical reality. Oseen understood the need for caution. He long despaired over the Academy and committee physicists’ lack of understanding of, and antagonism toward quantum theory. Now, with a brilliant strategic plan, Oseen recognized how he could overcome committee resistance to both Einstein and Bohr.

Oseen understood that he not only needed to be wary of the general lack of sympathy for quantum theory among Academy physicists, but he also had to overcome past committee evaluations. In particular, in 1921 Arrhenius wrote a short report for the committee on the theory of the photoelectric effect. He argued that regardless of Einstein’s genius-like insights, quantum theory was largely developed by others. Moreover, he concluded that it would seem odd to recognize Einstein for this considerably “less significant” accomplishment than for relativity and other work, such as related to Brownian motion. He recommended rejecting Oseen’s initial 1921 nomination for the discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect.

With Arrhenius’s prior assessment in mind and wanting to defuse potential opposition, Oseen closed his evaluation with a discussion on the relative significance of Einstein’s many accomplishments. Rejecting any universal hierarchy of importance, he suggests that each type of researcher considers its own preferred Einstein achievement as the most significant. He then provides a list, so that, for example, theoretical physicists might be drawn to Einstein’s contributions to quantum theory; mathematical physicists and epistemologists would be most attracted to the general theory of relativity. And for “the measuring physicist” —the type of physical scientist most represented and admired in the Academy—no work of Einstein’s can compete in significance with the discovery of a new fundamental law of nature, the law of the photoelectric effect.

Oseen then wrote an evaluation of Bohr’s quantum model of the atom. By emphasizing the very close bond between Einstein’s empirically proven fundamental law of nature and Bohr’s theory, Oseen overcame the committee’s earlier charges of speculative theory in conflict with the established laws of physics. Oseen convinced his colleagues in the committee to accept his proposals for the two physics prizes to be awarded in 1922.

When the Academy took up the committee recommendations, dissent emerged over the official motivation for Einstein’s prize. According to Mittag-Leffler’s diary entry, a long discussion ensued over competing suggestions for the wording. Finally, a proposal from conservative Former Prime-Minister, Hjalmar Hammarsköld “won”: relativity was not to be mentioned. This would indicate that further criticism of Gullstrand’s evaluation must have emerged. Mittag-Leffler, for one, wished to include both relativity and the discovery of the law in the official motivation for the prize. He disapproved as “a dangerous precedent” the vague general phrase relating to Einstein’s contributions to theoretical physics.

After the vote, the Academy made it clear that relativity should not be mentioned on the Nobel diploma or in any other official documentation.

Historigraphical Remarks

At the Nobel ceremony in December 1922, a tendency began of clouding the record of how the committee and Academy processed Einstein’s strongly supported candidacy (Einstein, who was away in Japan, did not attend). Of course, the statutes required secrecy, yet when Arrhenius delivered introductory comments about Einstein’s prize, he felt compelled to explain why the ever-so-prominent theory of relativity was not being recognized.

Although such ceremonial presentations are normally dubious sources for the history of discovery and of committee’s actions, Arrhenius’s presentation is especially problematic. He presented a misleading narrative. He explained the omission of relativity as it “… pertains essentially to epistemology and has therefore been the subject of lively debate in philosophical circles. It will be no secret that the famous philosopher [Henri] Bergson in Paris has challenged this theory, while other philosophers have acclaimed it wholeheartedly.”

The message here being that relativity belongs to philosophy and not physics. Regardless, if special and general relativity were at best philosophical exercises, why then did so many prominent physicists nominate Einstein for a Nobel physics prize for his work on relativity? Why, for example, did the Italians award their Medaglia Matteucci physics prize in 1921 to Einstein for relativity?

Arrhenius’s comments subsequently stimulated research and speculation on the role of Swedish philosophers’ attitudes to relativity and their relevance for the outcome in the Academy. Einstein’s differences with Bergson have even been declared to be the reason why relativity was denied a prize. Although Swedish philosophers debated relativity, no evidence exists that they had any influence on committee evaluations or Academy decisions.

In August 1981, the first detailed analysis of the Einstein prize, including the preliminary recognition of the critical roles of Gullstrand and Oseen, was presented at a Nobel Symposium and in Nature. An alternative and less controversial narrative was written the following year by Einstein biographer, Abraham Pais with the help of the secretary of the Nobel Committee for Physics, Bengt Nagel. This work is the origin of the mistaken claim that Einstein received a prize for the theory of the photoelectric effect as well as the simplified notion that Gullstrand merely made an unfortunate mistake in his evaluation as the reason for the lack of recognition of relativity.

While this certified — indeed let’s call it what it is — sanitized version of history is certainly the more pleasant, there is very little that we, as a scientific community, can learn from a simple “mistake”. The development of general relativity is one of the most impressive scientific feats of the 20th century. The fact that the community’s most prestigious scientific award never recognized this achievement is at best an anomaly and at worst a scandal.

When the time is taken to properly interrogate the deeply flawed process that led to relativity being snubbed, we can see the toxic effect of contemporary politics and bigotry on the science of the day. Whether or not a scientific advancement is worthy of recognition by the scientific establishment should have nothing to do with the race, gender, religion, social background, or the politics of the scientists involved.

These events occurred in the not-too-distant past. While much progress has been made in recent decades within academia to try eradicating bigotry and prejudice from science, we must accept that such pernicious influences can again creep into the community. It is incumbent on scientists to regard history as more than an opportunity for celebration. Only by embracing the full texture of science past and by remembering and understanding what took place not so long ago, can we protect against new incursions of ideas that are antithetical to the ideals we hold for science.

This article was originally published in Annalen der Physik’s ongoing “Then and now” series, which is dedicated to the history of physics. The article has been modified for this website version.

Access the full article here: Robert Marc Friedman, The 100th Anniversary of Einstein’s Nobel Prize: Facts and Fiction, Annalen der Physik (2022). DOI: 10.1002/andp.202200305