It is already widely known that the warming of the climate is causing a decline in essential crop yields such as grain, soybeans, and corn. And by taking the growing global population into account, the food security outlook is uncertain, if not grim. But the rising levels of CO2 in the atmosphere not only affect plants in terms of food availability — the nutritional content of food is also declining.

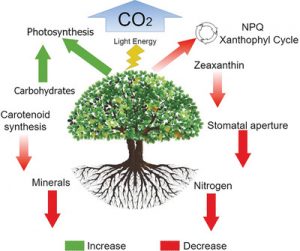

Another more subtle consequence of higher atmospheric CO2 (eCO2) concentrations is that plants grow thicker leaves, which are less effective at absorbing eCO2. Not only does this mean that more CO2 remains in the atmosphere — plants now produce more sugar as a result, diluting essential nutrients and negatively impacting human nutrition.

Mathematician Irakli Loladze has been a key researcher in elucidating the effects of eCO2 on plants and the plant ionome (its collection of minerals and trace elements). His curiosity on the subject was first piqued while attending a biology lab during his PhD studies, as he observed an experiment involving algae. Although photosynthesis was accelerated when more light was shed on the algae, it contained fewer nutrients, a finding that somehow seemed contradictory. Since plants rely on both sunlight and carbon dioxide, it seemed logical to suspect that rising CO2 levels would also have an impact on plant growth.

Propelled by this idea, Loladze later carried out statistical studies that confirmed this so-called “junk-food effect”: eCO2 reduces the mineral content in C3 plants (plants in which the initial product of photosynthesis is 3-phosphoglycerate, such as rice and wheat) and increases carbohydrate production. Moreover, this shift is both systemic and global in its significance; that is, the effect is observed in various plant tissues and occurs in temperate and subtropical/tropical regions.

In a recent paper published in Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, Loladze and his colleagues investigated the CO2-driven nutrient decline even further by addressing a novel question: Can rising CO2 levels affect human health by lowering carotenoid levels in plants, and in turn, human diets?

In a recent paper published in Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, Loladze and his colleagues investigated the CO2-driven nutrient decline even further by addressing a novel question: Can rising CO2 levels affect human health by lowering carotenoid levels in plants, and in turn, human diets?

Carotenoids are essential to human health for their antioxidant properties and are present in the colorful spectrum of fruits and vegetables we (hopefully) eat. An abundance of carotenoids (which includes xanthophylls and carotenes) in the diet has been linked to prevention of macular degeneration, cognitive decline, and chronic diseases.

The meta-analysis carried out by Loladze and his colleagues revealed that, similar to the downshift in plant minerals observed previously, a downshift in carotenoid concentration also exists. The mechanism by which this 15% decline occurs can be either passive (via dilution by carbohydrates, for example) or active (due to lower carotenoid synthesis as a result of lower carotenoid demands by plants).

Although more data is needed to address remaining questions, such as how changes in C3 plants compare to C4 plants and how abiotic stresses including drought, temperature, and excess light interact with CO2-induced carotenoid changes, this study provides an intriguing initial assessment of the phenomenon.