In order to make solar energy widely affordable scientists and engineers all over the world are looking for low-cost production technologies. Flexible thin film solar cells have a huge potential in this regard because they require only a minimum amount of materials and can be manufactured in large quantities by roll-to-roll processing. One such technology relies on cadmium telluride to convert sunlight into electricity. With a current market share that is second only to silicon-based solar cells CdTe cells already today are cheapest in terms of production costs. Grown mainly on rigid glass plates, these superstrate cells have, however, one drawback: they require a transparent supporting material that lets sunlight pass through to reach the light-harvesting CdTe layer, thus limiting the choice of carriers to transparent materials.

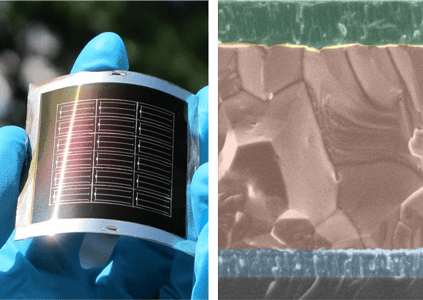

New progress paves the way for the industrialization of flexible, light-weight and low-cost CdTe solar cells on metal foils. Source: EMPA

The inversion of the solar cell’s multi-layer structure – the substrate configuration – would allow further cost-cuttings by using flexible foils made of, say, metal as supporting material. Sunlight now enters the cell from the other side, without having to pass through the supporting substrate. The problem, though, is that CdTe cells in substrate configuration on metal foil thus far exhibited infamously low efficiencies well below eight percent – a modest comparison to the recently reported record efficiency of 19.6 percent for a lab-scale superstrate CdTe cell on glass. (Commercially available CdTe superstrate modules reach efficiencies of between 11 and 12 percent.)

One way to increase the low energy conversion efficiency of substrate CdTe cells is p-type doping of the semiconductor layer with minute amounts of metals such as copper. This would lead to an increase in the density of holes as well as their lifetimes, and thus result in a high photovoltaic power. A perfect idea – if CdTe weren’t so notoriously hard to dope. “People have tried to dope CdTe cells in substrate configuration before but failed time and again”, explains Ayodhya Nath Tiwari, head of EMPA’s laboratory for Thin Films and Photovoltaics.

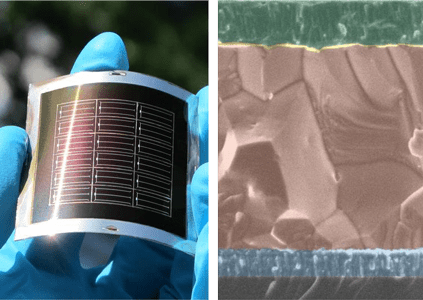

His team decided to try nonetheless using high-vacuum Cu evaporation onto the CdTe layer with a subsequent heat treatment to allow the Cu atoms to penetrate into the CdTe. They soon realized that the amount of Cu had to be painstakingly controlled: If they used too little, the efficiency wouldn’t improve much; the very same happened if they “over-doped”.

The electronic properties improved significantly, however, when the amount of Cu evaporation was fine-tuned to deposit a mono-atomic layer of Cu would on the CdTe. “Efficiencies increased dramatically, from just under 1 percent to above 12”, says team member Lukas Kranz. Their best value was 13.6 percent for a CdTe cell grown on glass; on metal foils Tiwari’s team reached efficiencies up to 11.5 percent.

For now, the highest efficiencies of flexible CdTe solar cells on metal foil are still somewhat lower than those of flexible solar cells in superstrate configuration on a special (and expensive) transparent polyimide foil, developed by Tiwari’s team in 2011. But, says Stephan Buecheler, a group leader in the lab: “Our results indicate that the substrate configuration technology has a great potential for improving the efficiency even further in the future.” Their short-term goal is to reach 15 percent. “But I’m convinced that the material has the potential for efficiencies exceeding 20 percent.” The next steps will focus on decreasing the thickness of the window layer above the CdTe, including the electrical front contact. This would reduce light absorption and, therefore, allow more sunlight to be harvested by the CdTe layer. “Cutting the optical losses” is how Tiwari calls it.

Source: EMPA