In 2023, the Earth’s average surface temperature was the warmest on record, beating out 2016, the previous warmest year. Now, the second annual Indicators of Global Climate Change report led by the University of Leeds has compounded this bad news.

The report confirms that human-driven or “anthropogenic” warming has risen 1.19 degrees Celsius over the 2014 to 2023 period. This is an increase from the 1.14 degrees Celsius anthropogenic warming seen from 2013 to 2022, which was set out in the first report.

“Our analysis shows that the level of global warming caused by human action has continued to increase over the past year, even though climate action has slowed the rise in greenhouse gas emissions,” said Piers Forster, director of the Priestley Centre for Climate Futures at the University of Leeds who coordinated the report. “Global temperatures are still heading in the wrong direction and faster than ever before.”

Forster said that the work combines many global measurements to make an authoritative update of factors that determine the human contribution to global warming and its trend. “We track emissions, atmospheric concentration levels, heat flows into the ocean, and surface temperature trends,” he added.

Though the aim of this report is to track long-term warming trends, the new report also looked at 2023 as a year in isolation, finding that the total amount of warming experienced last year was 1.4 degrees Celsius. The team was able to calculate that 1.3 degrees Celsius of this was attributable to human activity, and difference contributed to by El Niño conditions, which also played a role in 2023’s record temperatures.

Forster pointed out that this means that human-driven warming is increasing at an unprecedented rate of 0.3 degrees Celsius per decade. “Our results are in some way expected but nevertheless worrying,” Forster said. “The unprecedented rate of warming is the result of high levels of greenhouse gas emissions.”

What does this mean for greenhouse gas emissions?

The major contributing factor to human-driven climate change is the release of greenhouse gasses, predominantly carbon dioxide, via the burning of fossil fuels.

“Fossil fuel emissions are around 70% of all greenhouse gas emissions, and clearly the main driver of climate change, but other sources of pollution from cement production, farming and deforestation and cuts to the level of sulfur emissions are also contributing to warming,” Forster said.

In 2020, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) calculated that ensuring warming does not exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2030, the budget for the emission of carbon dioxide was in the range of 300 to 900 billion tons with a mid-range estimate of 500 billion tons in the ten years until 2030.

By the start of 2024, the remaining carbon budget for the 2030 warming target was estimated to stand at between 100 and 450 billion tons, with a central estimate of 200 billion tons.

The second annual Indicators of Global Climate Change report indicated that only 200 billion tons of carbon dioxide budget set in 2020 by the IPCC remains. That is around another five years’ worth of emissions.

This indicates that the high rate of warming experienced between 2014 and 2023 was caused by consistently high greenhouse gas emissions that are equivalent to the release of 53 billion tons of carbon dioxide per year during that period. Ongoing improvements in air quality also contributed to warming, reducing particles in the atmosphere and decreasing Earth’s albedo, the heat that our planet reflects back into space.

Is humanity doing enough to combat climate change?

Efforts are clearly being made to limit greenhouse gas emissions, but is humanity doing enough to combat global warming?

“Things have happened; renewable energy is replacing fossil fuels, and people are buying electric vehicles and installing heat pumps. Globally, increases in greenhouse gas emissions have slowed, and their emissions are still not above pre-pandemic levels,” Forster said. “Rapidly reducing emissions of greenhouse gasses towards net zero will limit the level of global warming we ultimately experience.

“Halving emissions by 2030 would halve the rate of warming. But global emissions need to fall, ultimately to zero, to halt the warming.”

He added that while most countries have promised action, many are simply not delivering enough. On June 5, the UN Secretary-General used the results of the second annual Indicators of Global Climate Change report in a speech yesterday to compel countries to take more urgent action.

The authors of the report hope that it will play a strong role in informing new improved climate plans that every country in the world has promised to put forward to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) by 2025 to cut emissions and adapt to climate impacts which are referred to as the Nationally Determined Contributions.

“Countries around the world need to take delivering on their net zero ambitions seriously,” Forster said. “ And the costs of inaction outweigh the costs of action.”

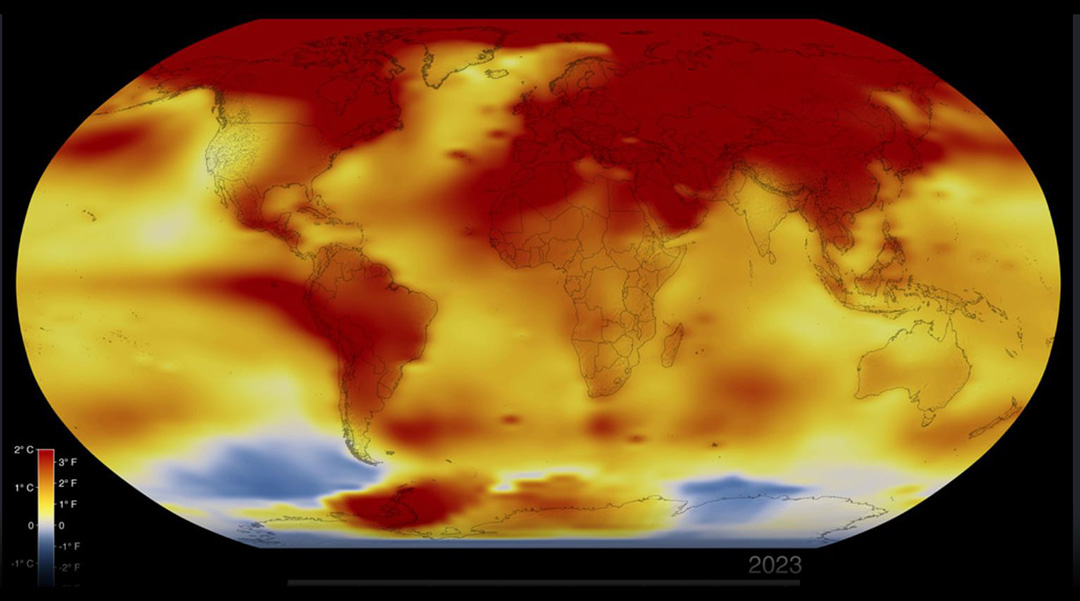

Feature image: A map of Earth in 2023 shows global surface temperature anomalies, or how much warmer or cooler each region of the planet was compared to the average from 1951 to 1980. Credit: NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio