Researchers have found a new way to combat contact lens-associated dry eye with a contact lens that contains a community of lubricant-producing bacteria.

For many people, contact lenses are an attractive alternative to traditional eyeglasses, but they do come with drawbacks. Contact lenses disrupt the eye’s tear film, which leads to friction between the lens and the surface of the eye, causing dry eye. This is a common problem for contact lens users, in fact, around 9% of those who discontinue using contact lenses cite dry eye as the reason.

“Contact lens-associated dry eye prevents contact lens wear and limits wear time,” said Aránzazu del Campo, scientific director and CEO of the INM-Leibniz Institute for New Materials in Germany. “The contact lens user needs to continuously use eye drops to restore the liquid and lubricant film on the contact lens surface.”

Bacterial biofactories

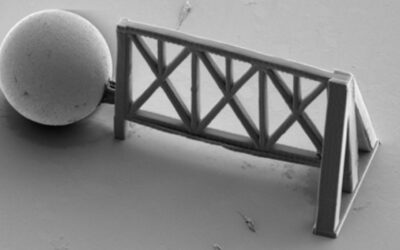

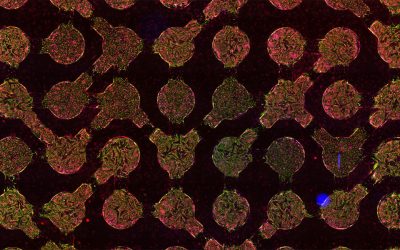

Bacterial biofactories are embedded in the rim of the self-lubricating lenses described in a paper recently published in Advanced Materials. The scientists, led by del Campo, engineered these bacteria to continuously produce hyaluronic acid, a natural lubricant.

Hyaluronic acid is already used in many commercially available contact lenses as it provides longer-lasting relief from dry eye than eye drops, which del Campo said tend to only help for a few minutes.

Still, lenses embedded with hyaluronic acid aren’t effective enough to completely solve the problem. Manufacturers can only add a small amount of lubricant before it starts to affect the optics of the lens, said del Campo, so relief may last for only a couple of hours at best and wearers may still find they need eye drops.

Bacteria capable of replenishing the supply of hyaluronic acid provide a simple solution to the problem. “The lubricant diffuses from the bacteria to the contact lens surface,” said del Campo.

“The self-renewal properties of the contact lens surface provides permanent lubrication despite continuous clearance of lubricant by tear fluid.” This eliminates the need for eye drops and lets the user wear the lens comfortably for longer periods of time.

The bacterium used in the study, Corynebacterium glutamicum, is a harmless species naturally found in soil. C. glutamicum does not produce toxins and is generally recognized as safe by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

It has been long valued for its ability to synthesize amino acids; in industry, it’s used to manufacture ingredients for a range of products from food flavorings to sun block. It has also been engineered to produce amino acids for the medical and pharmaceutical industries. “It is a workhorse for biotechnological production,” said del Campo.

C. glutamicum was chosen for the study not only because it could be engineered to secrete hyaluronic acid, but also because it serves as a model for the related species, C. mastitidis, a probiotic bacterium that is a natural resident of the human eye microbiome.

While commercial contact lenses supply the eyes with a limited amount of hyaluronic acid, C. glutamicum can make hyaluronic acid for as long as it’s able to obtain nutrients.

Getting consumers on board

In the study, the bacteria obtained nutrients from a simulated tear fluid. In a commercial product, the bacteria would get nutrients from the wearer’s tears and the overnight contact lens care solution. “In our experiments, hyaluronic acid production and therefore lubrication is maintained for weeks,” del Campo said.

“This technology is fascinating and promising, especially for patients who suffer from symptomatic dry eye while wearing contact lenses,” said optometrist Meenal Agarwal, who was not involved in the study. However, Agarwal also said she’s skeptical that the idea will gain widespread acceptance among patients.

“[The study] does not address the risks or safety concerns associated with having live bacteria in a contact lens,” she said. “Additionally, the study lacks discussion on contraindications for specific groups, such as immunocompromised individuals, and the safety risks of introducing live bacteria into their eyes.”

Further research will help establish safety or raise questions about any problems that might be associated with the use of the lens in human eyes, added del Campo.

“Our analysis [in the lab] shows that the living contact lens is [not harmful to cells]; [Live] studies are needed to rule out irritation or other problems,” she said. In their paper, the researchers also note that future studies will help them understand variables like bacterial density and nutrient concentration.

Once further research has established the safety and comfort of the new contact lens, the final hurdle will be consumer acceptance. While some may prefer to stick with what they know, others may find that the self-lubricating, living contact lens is a long overdue solution to an irritating problem.

Reference: Aránzazu del Campo, et al., Self-Lubricating, Living Contact Lenses, Advanced Materials (2024). DOI: 10.1002/adma.202313848

Feature image credit: Aránzazu del Campo, et al.