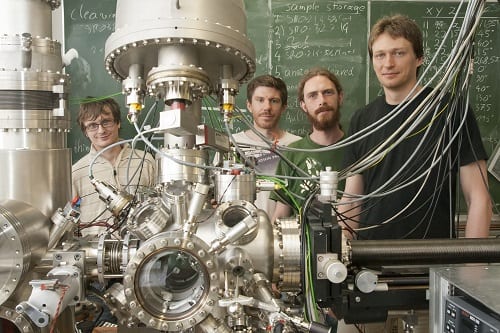

It can be found in toothpaste, solar cells, and it is useful for chemical catalysts: titanium dioxide (TiO2) is an extremely versatile material. Although it is used for so many different applications, the behavior of titanium oxide surfaces still surprises. Professor Ulrike Diebold and her team at the Vienna University of Technology managed to find out why oxygen atoms attach so well to tiny step edges at titanium oxide surfaces. Electrons accumulate precisely at these edges, allowing the oxygen atoms to connect more strongly. In solar cells, this effect should be avoided, but for catalysts this can be highly desirable.

It can be found in toothpaste, solar cells, and it is useful for chemical catalysts: titanium dioxide (TiO2) is an extremely versatile material. Although it is used for so many different applications, the behavior of titanium oxide surfaces still surprises. Professor Ulrike Diebold and her team at the Vienna University of Technology managed to find out why oxygen atoms attach so well to tiny step edges at titanium oxide surfaces. Electrons accumulate precisely at these edges, allowing the oxygen atoms to connect more strongly. In solar cells, this effect should be avoided, but for catalysts this can be highly desirable.

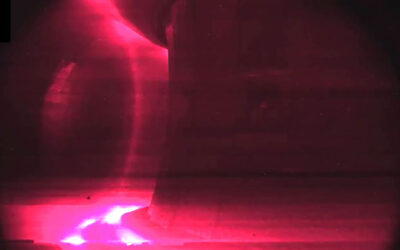

In the so-called Graetzel cell, an inexpensive but inefficient type of solar cell, titanium oxide plays the central role. “In a solar cell, we want electrons to move freely and not attach to a particular atom”, says Martin Setvin, member of Ulrike Diebold’s team.

The opposite is true for catalysts: for catalytic processes, it is often important that electrons attach to surface atoms. Only at places where such an additional electron is located can oxygen molecules attach to the titanium oxide surface and then take part in chemical reactions.

Usually, it takes a considerable amount of energy to have the electrons bond to a particular atom. “When an electron is localized at a titanium atom, the electric charge of the atom is changed, and due to electrostatic forces, the titanium oxide crystal is distorted”, as Ulrike Diebold explains. To create this lattice distortion, energy has to be invested – and therefore this effect does not usually occur by itself.

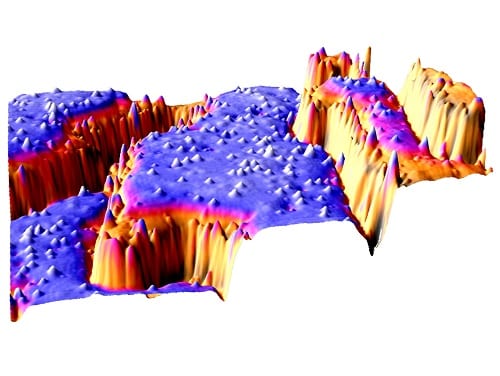

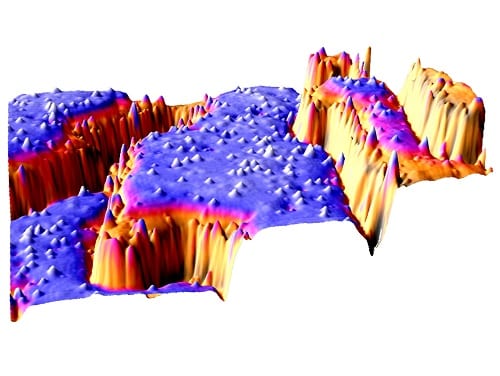

However, the surface of titanium oxide is never completely flat. On a microscopic scale, there are tiny steps and edges, many of them with a height of only one atomic layer. At these edges, electrons can localize quite easily. The atoms at the edge only have neighbors on one side, and therefore no major lattice distortions are created when these atoms receive an additional electron and change their charge state. “We have observed that oxygen molecules can connect to the surface precisely at these locations”, says Diebold.

However, the surface of titanium oxide is never completely flat. On a microscopic scale, there are tiny steps and edges, many of them with a height of only one atomic layer. At these edges, electrons can localize quite easily. The atoms at the edge only have neighbors on one side, and therefore no major lattice distortions are created when these atoms receive an additional electron and change their charge state. “We have observed that oxygen molecules can connect to the surface precisely at these locations”, says Diebold.

Important conclusions for technology can be drawn from this: for photovoltaics, such step edges should be avoided, for catalysts this newly discovered effect yields great opportunities. Surfaces could be microstructured to exhibit many such edges, making them extremely effective catalysts.