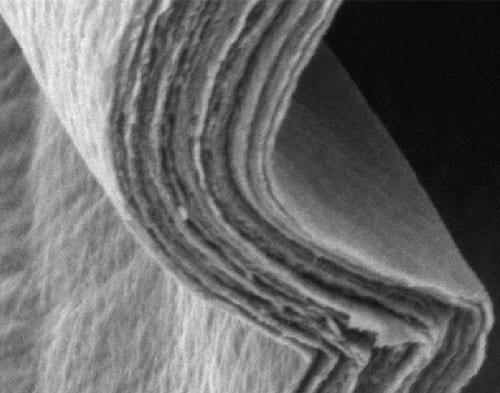

What material scientists have only learned in the last few decades, Mother Nature has practised for millions of years: transforming materials with rather modest mechanical properties into new, extraordinarily hard, tough and elastic ones, by giving them a sophisticated nanostructure. In molluscs’ shells, for instance, hard but brittle aragonite platelets are stacked in layers like bricks and joined using a protein “mortar”, thus creating the hard, yet elastic and sturdy mother-of-pearl.

This natural composite served as the model for the research carried out by scientists working with Žaklina Burghard and Joachim Bill from the Institute of Material Science at Stuttgart University, which is set up at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems on the Stuttgart Max Planck campus. Together with their colleagues from the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems and the Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research, they used the hard but brittle ceramic vanadium pentoxide to produce an elastic and electrically conductive paper.

First, the scientists synthesised nanofibres of vanadium pentoxide using water-soluble vanadium salt according to the procedure known for over 20 years. The rather unusual feature of this ceramic is that the fibres conduct electricity. This is possible because the metal oxide chains contain weakly bound electrons which can hop along them.

First, the scientists synthesised nanofibres of vanadium pentoxide using water-soluble vanadium salt according to the procedure known for over 20 years. The rather unusual feature of this ceramic is that the fibres conduct electricity. This is possible because the metal oxide chains contain weakly bound electrons which can hop along them.

The conductive fibres assembled into an elastic and strong paper – once the Stuttgart-based scientists had created the necessary conditions. They distributed the nanofibres suspended in water very thinly on a substrate, and afterwards let the aqueous film dry for several hours at room temperature, and then a few more hours at 40°C, slowly reducing the humidity in the climate chamber. This slow process allowed the fibres to assemble themselves into precisely parallel patterns. Finally, they annealed the film at 100 and 150°C, thus producing a transparent, orange paper whose thickness could be modified by changing the amount of nanofibre solution used.

“The paper can be folded like an accordion or rolled up,” Žaklina Burghard says. In this aspect, the ceramic paper is probably even superior to its natural model. “Although mother-of-pearl exists in small, helical sea shells in nature, this rigid biomineral cannot be folded like a normal sheet of paper.” The ceramic paper is not only more elastic than mother-of-pearl, it is also harder. What is more, it conducts electricity. “However, the conductivity along the paper fibres is much greater than across them,” Žaklina Burghard adds.

It is a combination of hard ceramic and soft water in the special nanostructure that makes the paper hard, strong and pliable. It also results in high conductivity in the paper plane and low out-of-plane conductivity. However, the electricity is not only transported by the electrons that move along the nanofibres, but also by ions in the water layers between the ceramic.

Both the electrical properties and the mechanical properties of the paper therefore vary according to the water content. By drying and annealing the material, the scientists mainly remove weakly bound water to make the ceramic fibres form a denser structure. Since this also reinforces the bonds between the nanofibres, it makes the paper harder and more rigid.

“Thanks to its excellent mechanical performance, combined with the electrical and chemical properties, the ceramic paper is suitable for numerous different applications,” as Burghard tells. For instance, ions could be incorporated between the vanadium pentoxide fibres and slabs, which would make the paper suitable as electrode material for batteries. “Since the paper is structured in regular and homogeneously shaped layers, ions can move efficiently in a particular in-plane direction,” Žaklina Burghard explains. Batteries with ceramic paper electrodes could therefore be charged quickly, but also discharged quickly to allow for high current densities. Industry is already showing a keen interest in using the paper in rechargeable batteries.

Furthermore, its capacity to accommodate ions makes the ceramic paper attractive to other fields. Since electrons can be made more mobile in vanadium oxide thanks to molecular interaction, it is also suitable for gas sensors. Owing to the small vanadium oxide nucleus, which has been reduced to just a few micrometres, instruments can be made smaller. In addition, the ceramic paper could give life to artificial muscles. When foreign ions accumulate in the composite, it expands. As an actuator controlled by the number of intercalated particles, the ceramic paper could push or pull objects down to microscopic size.