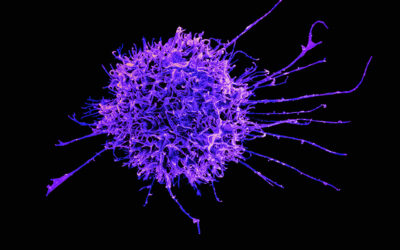

Poxviruses infect a wide range of species and utilize highly unusual replication strategies. Poxviruses that infect humans include the Variola Virus (VarV), the causative agent of smallpox that has killed more people than any other human pathogen combined.

Attempts to combat smallpox famously led to Edward Jenner’s development of the first vaccine, which ultimately enabled its eradication in the late 20th century. The vaccine strain, Vaccinia Virus (VacV) continues to be somewhat of an enigma as we remain unsure of its true origin.

Yet VacV is now considered the laboratory prototype for poxvirus research and is widely used as vaccine and gene delivery vectors in modern medicine. Other poxviruses infecting humans include Molluscum Contagiosum Virus (MCV), a widespread human disease with no cure.

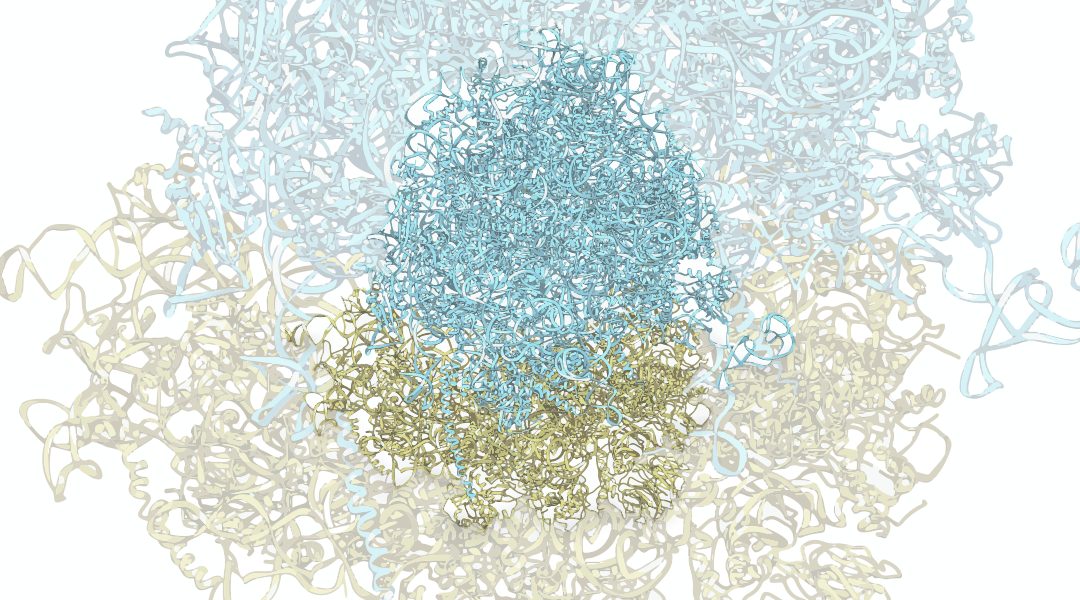

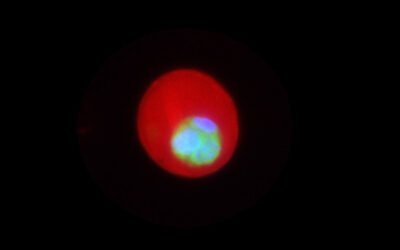

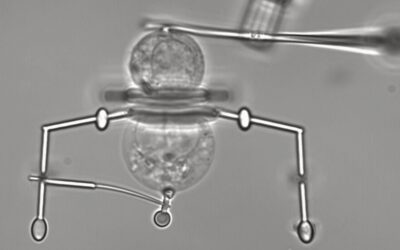

Poxviruses are very large double-stranded DNA viruses that encode hundreds of proteins including their own DNA replication and transcription machinery, mRNA biogenesis factors and even their own cytoplasmic redox system. Indeed, they are so self-sufficient that despite being DNA viruses they replicate in the cytoplasm of the cell.

However, despite this remarkable self-sufficiency they do not have the genetic coding capacity for the full complement of proteins needed for mRNA translation. For this reason, poxviruses go to great lengths to gain control of host ribosomes and regulatory translation factors while, in attempt to prevent poxvirus replication, host cells go to equally elaborate lengths to prevent the virus from access the translational machinery. In their WIREs RNA review, authors Derek Walsh, Nathan Meade, and Stephen DiGiuseppe discuss both viral and host strategies and how the fight to control translation is a major determinant of the outcome of infection.

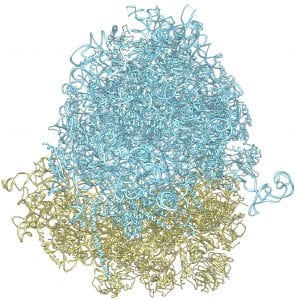

Kindly contributed by the Authors.