Climate change is impacting environments across the globe, but nowhere are these changes more evident than in cold regions, such as the Arctic and Subarctic. Rising temperatures, thawing permafrost, and disappearing glaciers are not only reshaping the landscape, but significantly altering northern water resources.

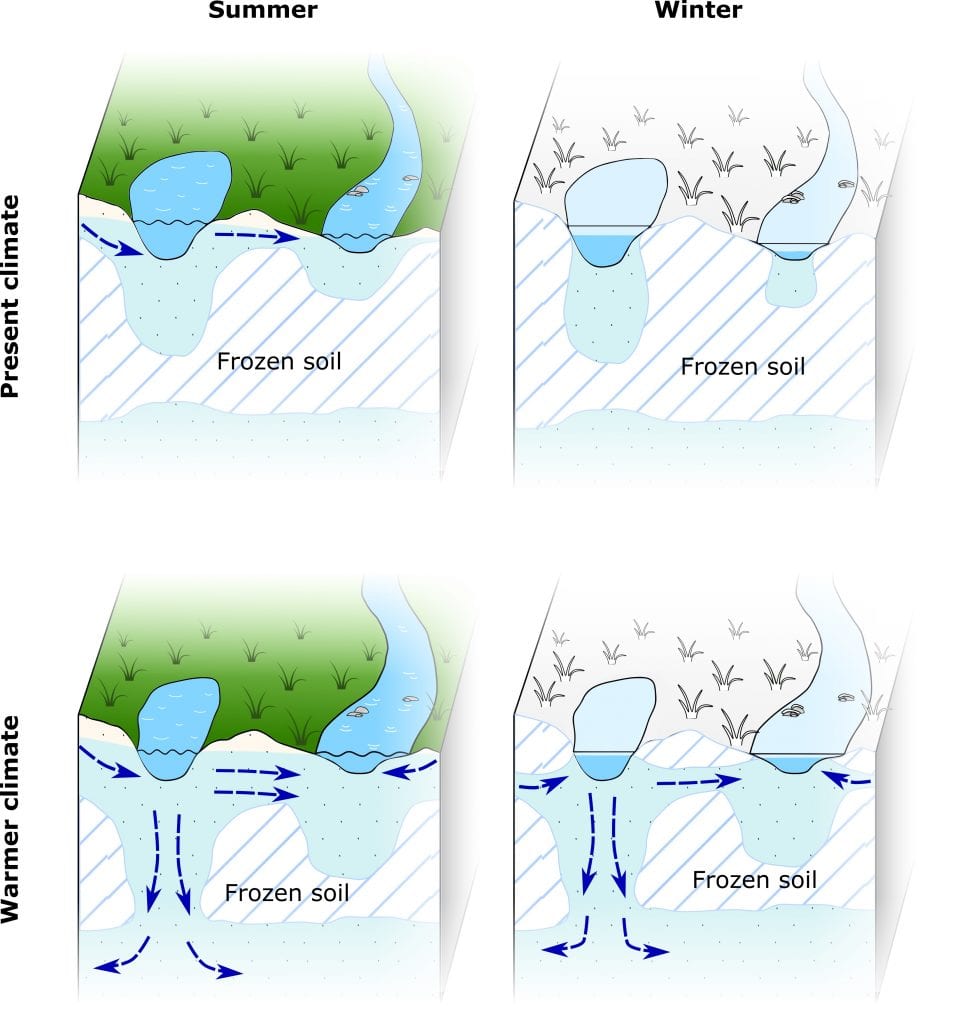

Permafrost is effectively impermeable and inhibits the flow of groundwater. As permafrost thaws, the potential for groundwater storage may increase, increasing the possibility of using groundwater as a resource. However, there are still many questions about the impact on groundwater systems of ongoing warming and thawing.

The use of groundwater in the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America is variable. In Canada, less than 5% of domestic use water in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut is from groundwater. In comparison, 99% of domestic use water in the Yukon is from groundwater, and approximately half of Alaskan residents rely on groundwater for their drinking water.

There are disadvantages associated with the use of groundwater as a water supply; aquifers recharge slowly and if contaminated they are very difficult to remediate. However, there are also may advantages; it is drought resistant, often has lower treatment costs, and can be pumped where needed.

With the uncertainty surrounding the future availability and vulnerability of lakes and rivers as a result of climate change, some communities and regions may begin to evaluate groundwater as an alternative or supplemental water resource. In order to make effective decisions about these matters, public policy officials must have access to modelling of groundwater systems that is as accurate as possible.

Numerical groundwater models have been used for over 40 years to understand the behavior and properties of groundwater, however almost none of these models are adapted for cold regions with permafrost. The mechanisms of ground freezing and thawing are complex, and the setup of these models requires data and parameterization of surface processes specific to cold regions. For example, the insulating effects of snow cover in winter are not typically included in groundwater models. These cold regions aspects of groundwater modeling make them difficult for users to apply.

Over the past decade, cryohydrogeology, the study of groundwater in cold regions, has emerged as an important subfield of Arctic and Subarctic hydrology. This has included the development of cryohydrogeologic models to simulate and understand changing cold regions groundwater and accurately model the movement of groundwater and heat as the ground freezes and thaws (see above). To date, cryohydrogeologic models have provided useful insights for scientists working in cold regions, but there has only been very limited application to real-world situations to develop effective water resource management plans.

The poor uptake of these models in public policy settings, may be due to their inaccessibility to non-academic users, and lack of clear guidelines on how to effectively use these modelling tools. A recent article by a Canadian team seeks to bridge this gap.

The team rigorously explain the background of cryohydrogeologic models; how they work, how they have been used so far, and give guidelines and tips for their effective use. This primer is aimed to help scientists and stakeholders adapt these models to suit their needs without needing to be a “modelling expert”.

Many changes are occurring in cold regions that are unique to the North American environment, and the more tools that are available to accurately guide public policy responses, the better.

Reference: Lamontagne-Hallé, et al ‘Guidelines for Cold‐Regions Groundwater Numerical Modeling’ WIREs Water (2020). DOI: 10.1002/wat2.1467