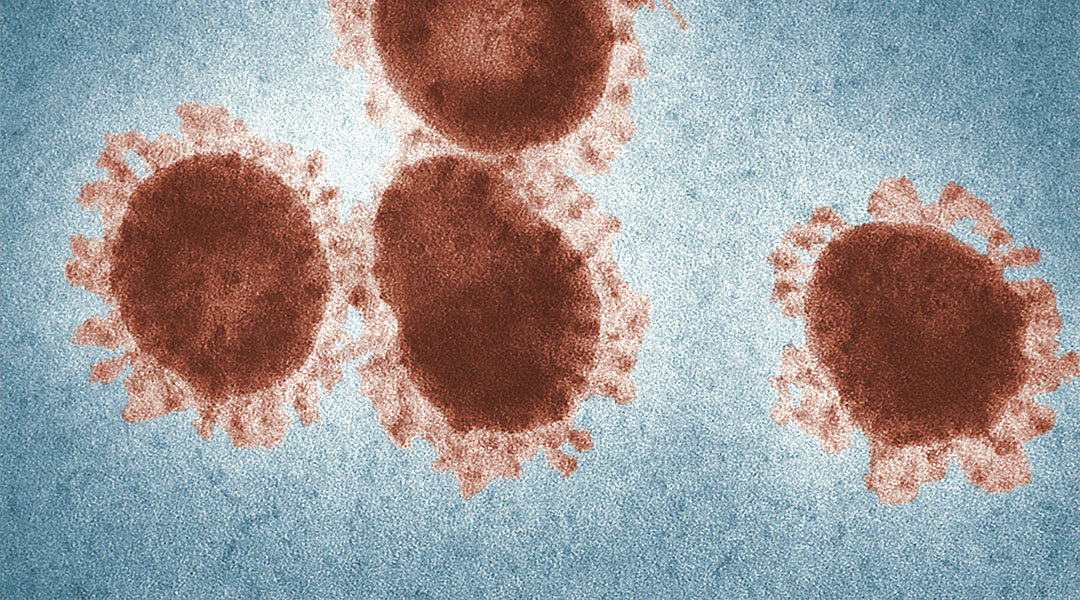

Today, scientists at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine have announced a potential vaccine against SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing the ongoing coronavirus pandemic.

Publishing in the Lancet-owned EBioMedicine, this is the first peer-reviewed research to be published on the subject of COVID-19 vaccines candidates, and is the product of a research team already familiar with vaccine developments of novel coronaviruses based on previous outbreaks. Speaking for a press release to the University of Pittsburgh, co-senior author of the research, Andrea Gambotto, explains how this has given himself and colleagues a head-start. “We had previous experience on SARS-CoV in 2003 and MERS-CoV in 2014. These two viruses, which are closely related to SARS-CoV-2, teach us that a particular protein, called a spike protein, is important for inducing immunity against the virus. We knew exactly where to fight this new virus.”

When tested on mice, the vaccine — dubbed PittCoVac — generated large numbers of antibodies in a couple of weeks.

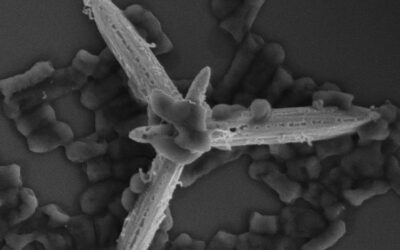

Whilst PittCoVac uses long-established methods for creating vaccines — using pieces of the viral protein to build immunity — instead of the more recent and experimental mRNA vaccine approach, the method of delivery uses more cutting-edge techniques: microneedle arrays.

The microneedle array developed by the Pittsburgh team comprises about 400 tiny needles on a small patch attached to a Band Aid. These needles deliver the COVID-19 spike protein pieces into the skin, and after time these microneedles dissolve away.

“We developed this to build on the original scratch method used to deliver the smallpox vaccine to the skin, but as a high-tech version that is more efficient and reproducible patient to patient,” said Louis Falo, the other co-senior author, in the same press release. “And it’s actually pretty painless — it feels kind of like Velcro.”

This manufacturing process is also scalable, which is a great advantage in these early stages. In normal times, scalability is usually lower down the list of priorities when developing new vaccines, just one of many factors why vaccines usually take so long to develop. But in times of a pandemic, scalability is important very early on in the process, and Falo and Gambotto’s team hit the ground running in this regard.

Back in the laboratory, whilst it is still too early to say whether the mice will have long-term immunity, the antibody surges seen at this two-week stage are comparable to that seen with the team’s MERS-CoV vaccine, which generated immunity for at least a year.

The team are in in the process of applying for approval from the US Food and Drug Administration so that human trials can begin in earnest. This process can take up to a year and longer, but Falo is optimistic this process might be a lot faster given the emergency situation. “This particular situation is different from anything we’ve ever seen, so we don’t know how long the clinical development process will take. Recently announced revisions to the normal processes suggest we may be able to advance this faster.”