In 2015, researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School developed a virus scanning technology called VirScan that can identify up to 1,000 viruses in a single drop of blood.

The revolutionary technique is similar to a standard blood test; however, rather than identifying one pathogen at a time, VirScan simultaneously scans for any virus known to affect humans, making it possible to test for current and past infections. It essentially provides a time capsule for researchers to look back and see what viruses a patient has experienced.

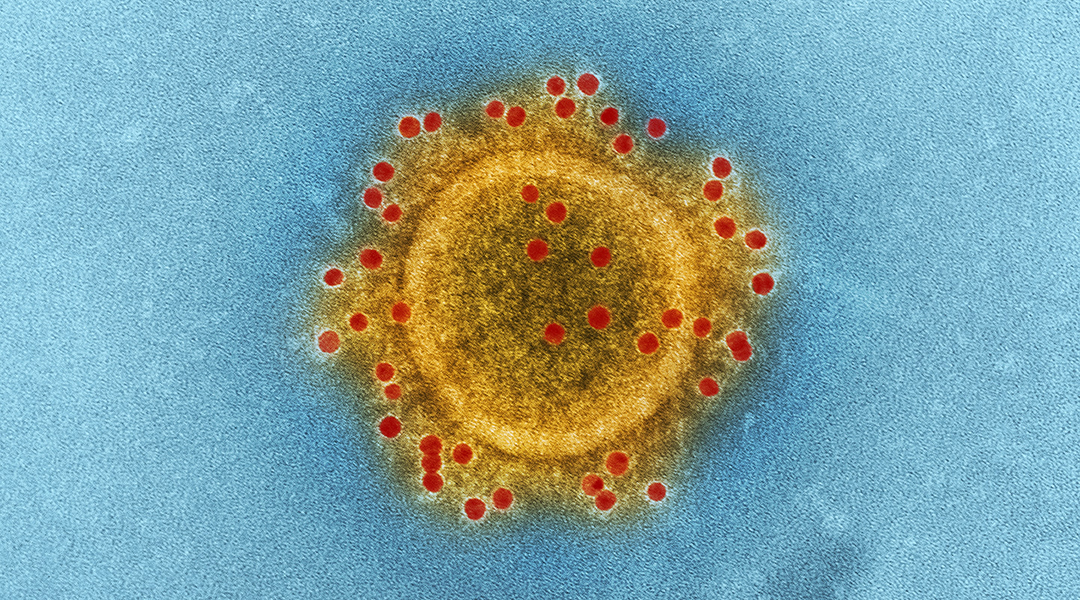

Now, scientists are adding SARS-CoV-2 to VirScan’s library to help combat the current pandemic. The team hopes that this addition could help facilitate the development of a desperately needed vaccine as well as provide a means of identifying undetected cases of the disease. Geneticist Steve Elledge, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator at Brigham and Women’s Hospital who led VirScan’s development, expects that the update should reach academic labs already using VirScan by mid-April.

“This is a community resource. It is all about making analysis of the coronavirus happen in real time in the places that need it,” said Elledge in a HHMI press release.

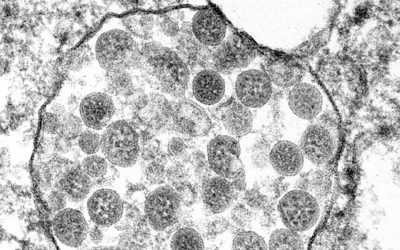

VirScan operates by screening for antibodies produced as a result of the body’s immune response, and which can remain in the blood for years after an infection. To build this library, Elledge and his team synthesized small genetic sequences of known viruses and then transferred them to bacteriophages, which are viruses that infect and replicate within bacteria.

Each bacteriophage is programed to produce one protein segment of viral DNA and display it on its surface. The team created hundreds of thousands of these DNA fragments for their scans, during which the collection of bacteriophages (each with it’s own unique fragment) interact with a sample of blood. Antibodies in the blood will find their target sequence, like a lock and a key, allowing researchers to identify which viral pieces of DNA were latched onto by sequencing the DNA of the bacteriophage, revealing which viral infections a patient had been exposed to.

To carry out the current update to VirScan’s library, scientists must first determine the integral parts of SARS-CoV-2 that antibodies will attach to in order for Elledge and his team to create the integral viral DNA fragments.

Many experts predict that the number of currently reported global infections is grossly underestimated because a significant number of cases remain undetected, likely because many people are asymptomatic. According to the HHMI press release, researchers recently estimated that 86 percent of infections in China in mid-January went undetected.

Elledge hopes that VirScan, although currently limited to the lab, could provide the basis for a rapid and standardized test for patients, overcoming the limitations of current tests, which rely on genetic material and cannot detect COVID-19 once a patient has recovered. According to Elledge, by creating a broad, robust testing platform, researchers could better identify how many individuals have been infected, which would allow them to better calculate the virus’ risk and spreadability, as well as how many people have acquired immunity.

This data could also help in producing a new vaccine and anti-viral therapies by allowing researchers to figure out which areas of the virus to target based on how patients’ antibodies latch onto VirSan’s fragements, essentially identifying SARS-CoV-2’s vulnerable spots, said Elledge.

In addition, VirScan contains other known coronaviruses, such as MERS and SARS, which can be used to compare how antibodies bind between different members of this family of viruses, making it possible to identify shared targets and repurpose known therapeutics or stimulate a similar immune response in currently affected patients.

While clinical trials of the earliest candidate vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 have already begun, Elledge says insights like these could inform later rounds to make vaccines more effective.