On 18 January 749 CE, a devastating earthquake struck parts of the Middle East. Cities were devastated and urban life changed profoundly across the region. The earthquake might even have contributed to the final fall of the Umayyad dynasty. One of the numerous cities hit, which did not return to its former prosperous state, was Gerasa/Jerash in the ancient Decapolis region, today’s northern Jordan.

Today, unexpected catastrophes, fluctuations in water availability, as well as profound but often slow climate changes still cause far-reaching and sudden changes, which severely alter a society’s ability to access water. This type of emergency calls for adaptable, water-management strategies – both immediate and long term.

In order to understand how modern societies might deal with water-management strategies come down to simple core questions: How does an urban society remain resilient to changes in water availability over a long period? What are the factors that create resilience? How and to what extent can society bounce back? And why do some urban societies survive natural disasters, such as earth quakes, and others not?

Ancient societies can provide us with the possibility to study such questions in order to glean crucial knowledge that may one day be valuable in aiding the recovery of modern societies that face challenges such as fluctuations in water availability due to climate changes.

Gerasa is one of these societies. Located in a semi-arid region in a spot with numerous natural springs and a river cutting through the city, it was fertile throughout the year. For life to be sustainable, fresh water is paramount, and maintaining installations to collect water was a fragile matter.

Investigating Gerasa’s water resources and water-management strategies from the early Roman period (first century CE) to the middle Islamic period (thirteenth century CE) has given us valuable insights into how the city sustained itself and dealt with natural threats to its water resources or threats, which were created by humans over time due to lack of knowledge about the negative environmental impacts.

The vulnerability and resilience of Gerasa with respect to its water resources has been tracked through the archaeological record. In a study published in WIREs Water, Professor Achim Lichtenberger of Münster University and Professor Rubina Raja of Aarhus University, who have headed an archaeological project in the city since 2011, explore Gerasa’s water-management strategies through time.

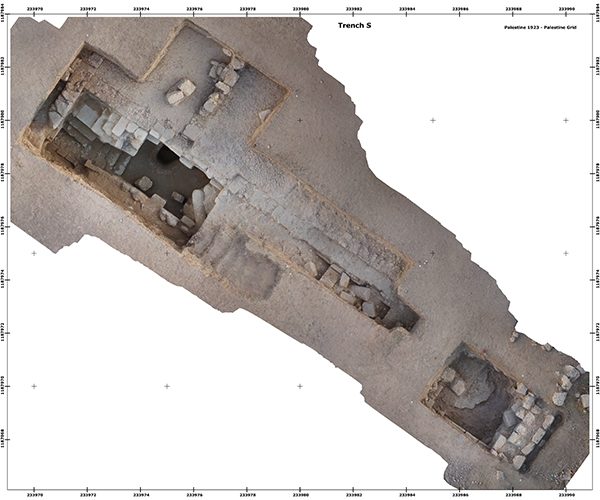

In order to come closer to understanding vulnerability and resilience of this ancient society, the various types of water installations, such as cisterns and water pipes, found in the city’s Northwest Quarter – the highest point within the walled city – have been examined. These include installations for running water (water-pipe systems), collected water (cisterns), and waste water (sewages), which were found.

In the early Roman period, the city had an extensive water-management system, and public authorities provided a centralized water supply. In the late Roman and Byzantine period, the water-pipe system was no longer in use, and it can be argued that water was not as available and easily manageable as earlier. This concurs with the so-called little ice age of the sixth and seventh century CE.

In early Islamic times, water was instead collected locally, and it became a private household matter to ensure access to water. After the earthquake of 749 CE, the water-management system was not reinstalled, and it is still remains to be explored how the small settlement of the middle Islamic period was supplied with water.

The longue durée investigations undertaken within the framework of the Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project directed by the authors give food for thought. According to the authors: “We learn about different strategies of using and maintaining water resources and about the ability of a society to embark on a new course when deemed necessary. The insights from this particular study as well as the continued research in Gerasa can give new perspectives on water-management strategies that may prove relevant for current societies in semi-arid regions struggling with vulnerable water systems.”