Currently, the Swiss Federal Act and Ordinance on Water protection require that substances that are not naturally present in surface water have concentration near-zero. Regarding pesticides, a single regulatory concentration of 0.1µg/l is given, which was set by experts based on pesticide detection limit in the 1980s.

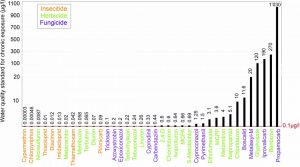

In November 2017, the Federal Department of the Environment, Transport, Energy, and Communications, which is in charge of defining strategies and efficiency targets for sustainable development, put consulted on a revision of the Federal Act on Water protection. It notably suggests modifying the regulatory concentration of 38 pesticides according to concentrations below which no adverse effect on any ecosystem is measured. Among the 38 suggested criteria, standards are raised for 12 pesticides and lowered for 25 others, sometimes with very high ratio. For example, the criterion value suggested for the herbicide Glyphosate is 1’200 times higher than the current standard.

In this WIREs Water review, two researchers of the University of Lausanne explore and discuss the influence of this legislative revision on the chemical status of a Swiss river. The General Directorate for the Environment of the Canton of Vaud provided concentrations of pesticides measured at three monitoring stations from 2005 to 2015. For each identified pesticide, risk coefficients based on the ratio of the pesticide concentration measured in the river to the water quality legislative standard and suggested criteria were computed. In each case, the worst-case value was retained to define the chemical status of the river.

Logically, the analyses showed that more pesticide concentrations are likely to meet the revised criteria, thus implying a better chemical status. On average, every year, 70% and 90% of the pesticides identified met the legislative standard and suggested criteria, respectively. Based on the current legislative standard, the chemical status of the river was defined as moderate to poor whereas based on the suggested criteria, its chemical status was mainly good.

As acknowledged by the Federal Office for the Environment, the authors argue that increasing the criteria value for a large number of pesticides will raise the level of tolerance of pesticide concentration in rivers and will reduce the number of exceedances of the criteria. However, the presence of herbicides was currently identified as the main pollution issue in the studied river, but raising standards also revealed pollution by insecticides, and therefore new risks for sensitive species.

The authors hence support that water quality standards for pesticides should be as strict as possible. If effects of some pesticides on aquatic species are identified at concentrations below 0.1µg/l (for example, Chlorpyrifos and Diazinon as identified in this study), the authors encourage raising standards for these substances. Otherwise, based on the precautionary principle and the philosophy of Swiss Federal Act and Ordinance on Water Protection, they recommend keeping the historical standard.

Furthermore, the authors claim that research strategies and chemical analyses taking into account mixture of pesticides and multigenerational effects should be further assessed to accept increasing water quality criteria for pesticides. Finally, practical solutions exist to reduce pesticide use and improve water quality and have proved fruitful in the studied river. They should be further supported.