Onboard the International Space Station (ISS), one liter of water costs more than 10,000 Euros. The inhabitants therefore use water cycle with the aid of a water recovery system, an on-board sewage treatment unit that recovers water from the astronauts’ toilet, washing facilities and air conditioning. On earth, water is not as expensive, but more and more people recognize the value of water and demand a circular economy, however, a more biological cycle.

Circular economy to keep vital resources

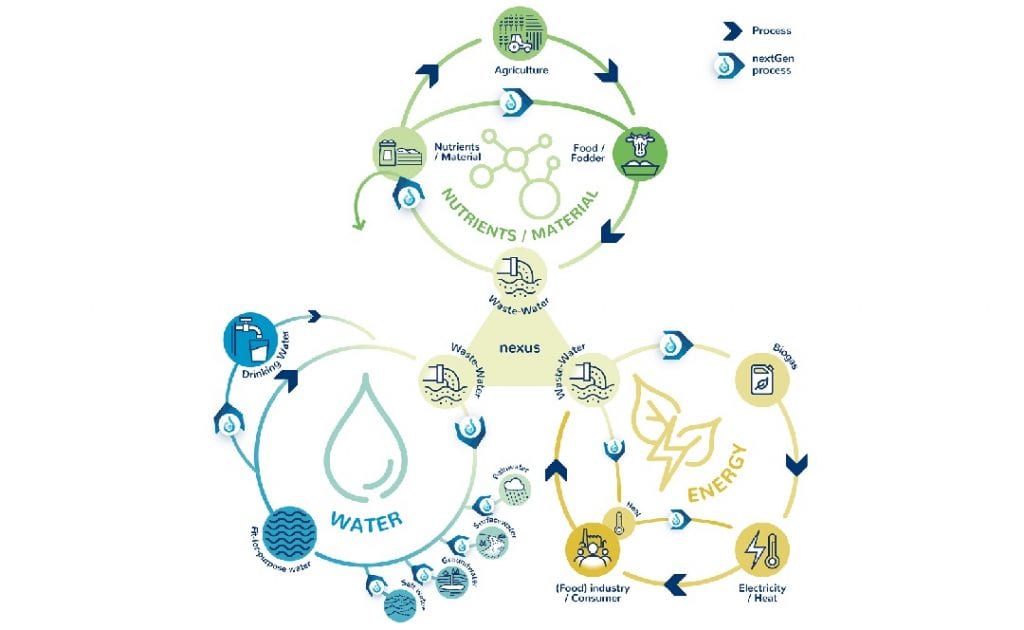

Today and likewise in the past, water is usually withdrawn from rivers, reservoirs, and groundwater for use in agriculture, industry, society, and the environment, and is then returned to the water basin directly or via a treatment facility. Unfortunately, this current system is often inefficient as water is lost, polluted, and wasted, which is becoming an increasing problem since more and more regions that were never before threatened by water shortages are falling dry. But in recent years, society and business have started to develop a system that is “closed looped” to increase efficiency and optimize reuse.

The circular economy keeps resources, such as water, at its highest value at all times with the idea of breaking down the connection between growth and finite resource consumption. Creating a circular economy for water offers great opportunities, but also inherent challenges, as recently outlined in a study published in WIREs Water. According to the authors, the key to a successful transition to a more circular economy requires active involvement from all members of society and strong levels of collaboration.

Communities of practice to enable circular economy

Jos Frijns, scientist at the Dutch KWR Water Research Intitute, and his co-authors see communities of practice as a suitable approach to establish circular economy water technologies. These are social learning systems that bring together people who share a concern or a passion and provides a means for improving their practices through shared involvement.

“The transition to a circular economy requires participation of all relevant stakeholders,” said Frijns. “Communities of practice are an effective way to organize this participation as they provide for actual engagement, exchange of opinions and experiences, and collective learning.”

They also enable diverse stakeholders to engage and share different perspectives, interests, and needs, and ultimately, to co-produce knowledge. It is a management tool through which members share insights as well as frustrations, critiques, or adoption of each other’s practices.

Opportunities and challenges of communities of practice

The water sector has serious problems which are predicted to increase as a result of climate change and increasing urbanization — it is therefore hardly possible to meet these challenges without intense cooperation of society and industry. The involvement of relevant stakeholders dealing with water management, regulation, and consumption is essential for the transition towards a circular water economy, however, it is not an easy process.

“Communities of practice need to be organized and well facilitated, otherwise they end up either as time-consuming gatherings without any social learning,” Frijns pointed out. It takes time for stakeholders to build trust and understanding to work successfully together.

Bringing research to life

The H2020 project NextGen intends to demonstrate innovative technological, business, and governance solutions for water in the circular economy in multiple cases across Europe. Frijns who is coordinator of NextGen explained: “At each demo case, a community of practice is set up to promote a multi-stakeholder approach to discuss circular economy water technologies in its institutional context. The community’s aim is to create an engagement environment around the demonstrated innovations in which stakeholders across the water value chain interact and collaborate.”

NextGen brings together representatives from the water industry, authorities, engineering companies, consultants, research institutes, representatives of non-governmental organizations, and potential end-users like in Gotland one of the demo cases. In recent years, the Swedish island has experienced a severe water crisis that negatively affected tourism and industries.

“New conditions like water scarcity, climate change, transition to sustainable society, etc. require new solutions that might not come from above but rather to be rooted in all levels to be successful,” explained Ewa Lind, NextGen lead for Gotland. She has held several very successful engagement sessions with local stakeholders, such as farmers and citizens. “Participation and seeing your own benefit is absolutely necessary for a success in this type of project. Laws, policies and governance need to be adapted to the new solutions to both simplify and speed up the transition,” she stated.

Community of practice could benefit other disciplines

Water management institutions, researchers, and technology developers are realizing the importance of co-producing interdisciplinary research with the aim of developing more integrated and circular resource management and governance approaches. The participation of stakeholders across policy sectors and geographical scales, and the inclusion of different perspectives, interests, and needs, are important requirements to effectively upscale the circular economy framework in the water sector as seen in the NextGen project.

“We hope that our work is of benefit to other disciplines on how to organize stakeholder engagement in transition processes towards sustainability or circular economy,” concluded Frijns.

Reference: A. Fulgenzi, et al. ‘Communities of Practice at the centre of circular water solutions.’ WIREs Water (2020). DOI: 10.1002/wat2.1450