Two million years ago, on the edge of a hot spring in the continent that would become known as America, a single celled organism named Clinton ran out of food. Clinton was an acidophile, a microbe who thrived in battery-acid-like conditions, but he was not built for starvation. He shifted about the best he could, looking for a decent feed. Some days he found a tasty snack, but never enough to be truly satisfied. One cloudy humid day, Clinton hiccuped and passed away.

For researchers trying to understand the environmental conditions that Clinton found himself in, his decaying cell could be a treasure trove of information. “Biomarkers, like the fat molecules that make up the cell membranes in our own bodies, can be powerful recorders of the environment that can last for billions of years,” says William Leavitt, a scientist who studies ancient microbes.

If researchers knew which biomarkers to look for they could examine the cell membrane of a character like Clinton and reliably infer whether he lived his life in famine or feast.

This type of analysis has been done on the remains of single celled organisms that lived in benign conditions like oceans and lakes. However, until recently the tools to examine acidophiles did not exist.

Leavitt’s team recently took the first steps in that process by varying the amount of sugar available to acidophiles living in a bioreactor that simulated the conditions at the edge of a hot-spring.

“This bioreactor-based approach was unique because it allowed us to fully isolate the effect of limiting sugar to these microbes,” explains Alice Zhou, one of the scientists involved. “This is different from the vast majority of microbiology experiments that are conducted in closed-system batch cultures, where multiple variables such as solution chemistry and population size change over time and confound results.”

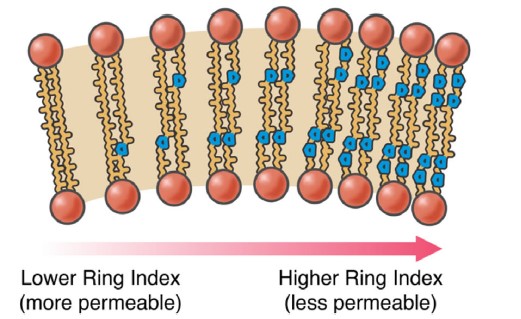

The microbes that were starved showed a distinct chemical signature in their cell membranes. They contained more of a molecular constituent called a “cyclopropyl” group. This group allows the cell membrane to pack together more tightly (see above). This closely packed membrane is better able to prevent unwanted loss of energy rich ions, keeping as much energy as possible within the cell.

Researchers working with the remains of ancient acidophiles could use this chemical signature to infer whether the microbes’ environment was nutrient-rich or nutrient-poor, one more piece in the puzzle of ancient ecology. As Leavitt argues, “It’s critical that we are as careful as possible when we interpret the geological record. It is pretty rare that there is just one factor at play. We need to understand all the parameters before we make big-picture projections.”

Research article found at: A. Zhou, et. al. Environmental Microbiology, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.14851