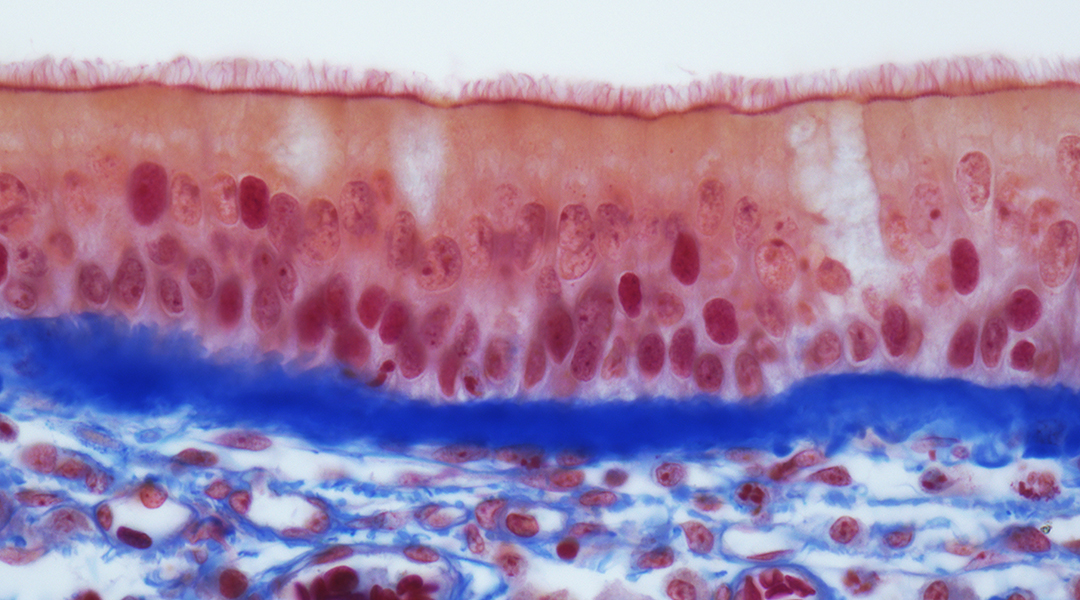

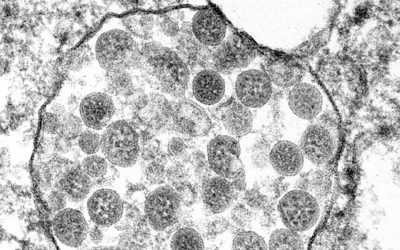

Scientists from the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH), Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Thorax Clinic at Heidelberg University Hospital have examined samples from non-virus infected patients to determine which cells in the lungs and bronchi are targets for novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) infection. They discovered that the receptor for this virus is abundantly expressed in certain progenitor cells, which normally develop into respiratory tract cells lined with hair-like projections called cilia that sweep mucus and bacteria out of the lungs. The scientists have now published their findings in The EMBO Journal.

Professor Roland Eils and his colleagues from the Thorax Clinic in Heidelberg initially intended to study why lung cancer sometimes occurs in people who have never smoked. They began by analyzing samples of twelve lung cancer patients from both the cancerous part of the lungs and the surrounding healthy tissue. They also studied cells from the airways of healthy patients. The rapidly spreading coronavirus prompted the researchers to take another look at this existing but so far unpublished data. “I was convinced that the data we gathered from these non-coronavirus infected patients would provide important information for understanding the viral infection,” says Roland Eils, founding director of the BIH Digital Health Center.

“We wanted to find out which specific cells the coronavirus attacks,” explained Professor Christian Conrad, who also works at the BIH Digital Health Center. The scientists knew that the virus’s spike protein attaches to an ACE2 receptor on the cell surface. In addition, the virus needs one or more cofactors for it to be able to penetrate cells.

But which cells are endowed with such receptors and cofactors? Which cells in which part of the respiratory system are particularly susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection?

“We then analyzed a total of nearly 60,000 cells to determine whether they activated the gene for the receptor and potential cofactors, thus in principle allowing them to be infected by the coronavirus,” reported Soeren Lukassen, one of the lead authors of the study. “We only found the gene transcripts for ACE2 and for the cofactor TMPRSS2 in very few cells, and only in very small numbers.”

“Armed with the knowledge of which cells are attacked, we can now develop targeted therapies,” explained Professor Michael Kreuter from the Thorax Clinic at Heidelberg University Hospital.

Why does the infection progress so differently?

An interesting additional finding of the study was that the ACE2 receptor density on the cells increased with age and was generally higher in men than in women. “This was only a trend, but it could explain why SARS-CoV-2 has infected more men than women,” Eils said. “[However], our sample sizes are still much too small to make conclusive statements, so we need to repeat the study in larger patient cohorts.”

“These results show us that the virus acts in a highly selective manner, and that it is dependent on certain human cells in order to spread and replicate,” Eils explains. “The better we understand the interaction between the virus and its host, the better we will be able to develop effective counter strategies.” He and the other researchers will next study COVID 19 patients to ascertain whether the virus has actually infected these cells. “We want to understand why the infection takes a benign course in some patients, while causing severe disease in others,” Eils said. “So we will also look closely at the immune cells in the infected tissue.”