Stress can be good for you – it helps you survive; on the other hand, it is well-known that stress can also increase your risk of developing certain psychopathologies ,including anxiety and depression. However, what really happens in a stressed brain at the molecular level has not been fully characterized.

Over the past few decades, it has been shown that in addition to small molecule neurotransmitters, hundreds of neuropeptides act as important signaling molecules in the nervous system. In an article in Proteomics, researchers led by Gregor Rainer, Fribourg University, Switzerland, show how different stress events encountered during the development and in adulthood influence the secretory peptidome of two rat brain regions.

Peripubertal rats were exposed to a synthetic fox scent and further challenged with an elevated platform; adult rats were stressed by the acute restraint stress procedure which involves gently wrapping the rats in a paper towel to minimize the risk of injuries and restraining their movement for an hour in wire mesh restrainers.

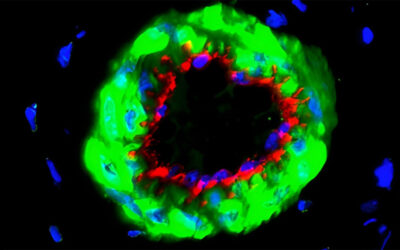

A comprehensive, quantitative analysis of control rats’ and stressed rats’ brains was performed to characterize the neuropeptidomes in the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex.

The analysis showed that different neuropeptides were regulated in the two regions: in the hippocampus, Met‐enkephalin, Met‐enkephalin‐Arg‐Phe, and Met‐enkephalin‐Arg‐Gly‐Leu were upregulated, while Leu‐enkephalin and Little SAAS were downregulated after stress. In the prefrontal cortex, Met‐enkephalin‐Arg‐Phe, Met‐enkephalin‐Arg‐Gly‐Leu, peptide PHI‐27, somatostatin‐28 (AA1‐12), and Little SAAS were downregulated. This shows that the modulation of neurochemical circuits triggered by stress is brain area-specific.

These findings have important implications for the development of therapeutics, and several potential pharmacological targets for the treatment of stress‐related disorders have been identified.