Scientists have found that the nutrients our immune cells feed on can make or break their ability to fight infections and cancer. This discovery draws a previously unknown connection between which genes are activated in a cell and the nutrients it relies on.

“You know the saying, ‘You are what you eat?’ We wanted to know, ‘Is the cell what it eats?'” said Susan Kaech, professor at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and senior author of the study.

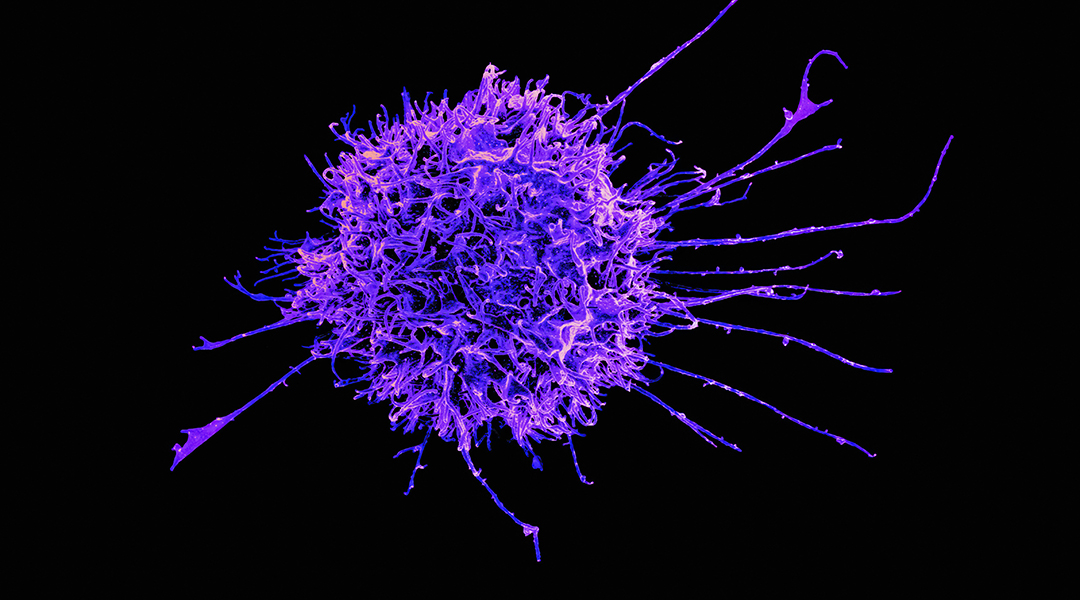

Kaech and colleagues were studying a type of immune cells known as effector T cells, which are responsible for identifying and fighting pathogens and tumors. When these cells are activated for long periods of time, they can enter an “exhausted” state where their ability to fend off threats is reduced.

The scientists noticed that as these immune cells become exhausted, they switch from preferring to feed on one nutrient to another. Reverting this change in feeding habits prevented the cells from getting exhausted.

This newly found link between cell nutrition and function could be a promising target for therapies aiming to prevent immune cells from becoming exhausted. What’s more, the discovery opens the door for droves of new research looking for more examples of these connections.

“What we discovered is fundamental to any cell, because all cells use nutrients,” said Kaech. “We’ve just uncovered the tip of the iceberg.”

Fighting exhaustion

Studying the nutrition of cells has been of great interest to cancer research over the past decade. Cancer cells are known to have different nutritional needs to healthy cells, such as requiring higher amounts of sugar to sustain their growth, revealing a “weakness” that can be exploited against them.

Kaech’s research group, however, was interested in looking at the nutrition of the immune cells that fight tumors instead, as not much is known about how changes in the nutrients they feed on can affect their function. In particular, they wanted to know more about how nutrition is linked to immune cells becoming exhausted.

“One of the major goals of cancer research is to develop therapies that eliminate T cell exhaustion,” said Kaech. “If we can prevent T cell exhaustion from happening, that could result in stronger, more robust immune responses against the tumor.”

The scientists were looking at a specific molecule called acetyl-CoA that plays an important role in turning genes on and off within the cell. Our cells can synthesize this molecule from a variety of different nutrients, and they were interested in seeing if that made a difference.

What they found was that functional T cells prefer to feed on a nutrient called acetate to make acetyl-CoA. However, as they become exhausted they progressively lose the ability to feed on acetate and instead increasingly rely on another nutrient, citrate, to make acetyl-CoA.

Our cells rely on different proteins to make acetyl-CoA from either acetate or citrate. The scientists found that these proteins are found in different locations within the cell’s nucleus, where the DNA is stored, which in turn resulted in altering the activity of different genes found at different locations.

“The cells cared about which nutrient was used to generate acetyl-CoA,” said Kaech. “We didn’t expect that.”

A new therapeutic target

Previously, scientists thought that once a T cell becomes exhausted, it cannot revert to a functional state. However, this new discovery shows that it might actually be possible to reprogram these immune cells by changing what they eat.

The researchers tested two strategies to force T cells to feed on acetate over of citrate to make acetyl-CoA, which successfully prevented the cells from becoming exhausted. The first one consisted in engineering the cells to produce more of the protein that turns acetate into acetyl-CoA. The second relied on blocking the protein that turns citrate into acetyl-CoA, which the cells would naturally compensate for by consuming more acetate.

“This showed us a new, interesting way to reprogram immune cells and make them better at fighting cancer,” said Kaech.

She pointed out that drugs that block cells from feeding on citrate are already in use as cancer treatments because they can also stop cancerous cells from growing. Her group’s discovery shows these drugs could be used to simultaneously prevent tumors from growing and helping immune cells fight for longer.

In addition to exploring therapeutic strategies that target the nutrition of the cells, Kaech and colleagues want to start looking for other similar links between nutrients and cell types, which could extend way beyond immune cells.

“We uncovered one way for nutrients to regulate the cell,” she said. “There are probably lots of other processes in our cells doing the same thing.”

Reference: Shixin Ma et al., Nutrient-driven histone code determines exhausted CD8+ T cell fates, Science (2024). DOI: 10.1126/science.adj3020

Feature image credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases on Unsplash