As the world continues to closely monitor the newest coronavirus outbreak, the government of South Korea has been able to keep the disease under control without paralyzing the national health and economic systems. In a new research article published in The American Review of Public Administration, University of Colorado Denver researcher Jongeun You reviewed South Korea’s public health policy to learn how the country managed coronavirus from January through April 2020.

Testing Timeline

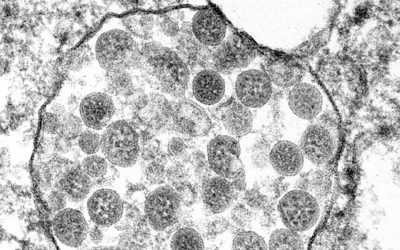

In January, the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in partnership with the Korean Society for Laboratory Medicine and the Korean Association of External Quality Assessment Service, developed and evaluated the real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) diagnostic method for coronavirus.

By February, the diagnostic kit was authorized, and as of March 9, 15,971 kits were produced, capable of testing 522,700 people.

As of April 15, South Korea has tested 534,552 people for coronavirus, which is 10.4 people per one thousand population. South Korea also operated 600 screening centers (including 71 drive-through centers), and more than 90 medical institutions assessed specimens with an rRT-PCR test.

According to You’s research, the critical factors in South Korea’s public health administration and management that led to success include national infectious disease plans, collaboration with the private sector, stringent contact tracing, an adaptive health care system, and government-driven communication. The South Korean government proactively found patients who contracted coronavirus, disclosed epidemiologic findings of confirmed patients to the public, and provided differentiated treatments based on the severity of symptoms. Unlike other major nations, South Korea has a mostly homogenous cultural and institutional structure, which enabled the policies put in place by the government to become effective.

The Three Major Keys to South Korea’s Success

South Korea conducted rigorous and extensive epidemiologic field investigations for coronavirus cases. This process included interviews with patients and triangulation of multiple sources of information (e.g., medical records, credit card and GPS data). The Institute for Future Government’s survey in 2020 found that 84% of South Koreans accept the loss of privacy as a necessary tradeoff for public health security.

South Korea is a democratic unitary political system. The local governments have limited autonomy and its public health governance is centralized, enabling South Korean agencies to act quickly to implement policy decisions at the local level. After the MERS outbreak in 2015, the South Korean government expanded legal and administrative boundaries regarding pandemic responses, enabling public administration to acknowledge the different procedures. For example, the Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act was amended significantly to prevent infectious disease and secure the public’s right to know through surveillance and tracing techniques.

Lastly, the public health budget and flexible fiscal management systems allowed the South Korean government to provide adequate resources. The South Korean government and national health insurance program shouldered the full cost of coronavirus testing, quarantine, and treatment for Korean citizens and noncitizens. Furthermore, on March 17, 2020, the South Korean Legislature passed the supplementary budget of 11.7 trillion KRW ($10.1 billion) in 12 days. The Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare’s (KMHW) supplementary budget passed in March 2020 is 3.7 trillion KRW ($3.2 billion), which enabled the KMHW to increase COVID-19 prevention and treatment facilities and to support medical institutions and workers.

United States Viability

“There are many variables to consider when emulating policies from other countries,” said Jongeun You. “South Korea’s extensive surveillance and contact tracing using ICT (information and communications technology) may not be applicable at the federal level in the U.S. due to different cultural norms.”

According to You, what the United States could have adopted from South Korea was its ability to quickly ramp up its testing capacity. As mentioned above, South Korea had testing capabilities by end of January after a fast review from the Korean FDA. In the United States, on February 12, 2020, when public and private labs had not yet received FDA approval for their own tests, the CDC revealed that a CDC-designed test kit contained a faulty reagent.

You suggests the public administrators need to meticulously document everything–and in a timely manner. Using this information, administrators must go one step further and update policy regarding key lessons learned.

“Though many solutions are emerging, I believe one essential solution for public administrators is to collect documentation about their successes and struggles, and what they hear from citizens and residents about policy implementation and communication.”