Image credit: Kiara Worth

Six years after the historic Paris Agreement was made to avoid the most disastrous effects of climate change by limiting global warming, delegates, leaders, activists, and scientists from over 200 countries will be meeting this week in Glasgow for the 26th Conference of Parties (COP26) climate change conference.

The event will last two weeks (Oct. 31-Nov. 12), hosting a number of events and discussions aimed at assessing how well nations are fairing in the face of a visibly changing climate. What has and hasn’t been achieved will be on the table, along with new discussions around making concrete plans to reach the agreed upon targets. This year’s conference is highly anticipated given that countries are now putting forth newer, more stringent commitments to make further gains when it comes to reducing global emissions.

“The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare and further exacerbated global inequality, while loss and damages from climate impacts have increased in frequency and severity,” said Alicia Seiger, managing director of the Precourt Institute for Energy’s Sustainable Finance Initiative at Stanford University, in a statement. “This will be the first large in-person climate conference to take place in the midst of such intense pressure. I hope that results in new and major breakthroughs, but we could see unrest.”

The world is not on track

The Paris Agreement is a legally binding treaty in which signing countries agreed to “pursue efforts” to limit global heating to 1.5°C. Climate conferences have been taking place since the first World Climate Conference held in Geneva in 1979. While some might argue that they seem performative, experts indicate that there have been tangible outcomes underscoring their importance.

“In broad terms, before [the Paris Accord], it was looking like the world was going to get to 3.6 by the end of the century, but Paris has essentially dragged that down to 2.6°C — taking the IEA’s latest numbers,” said Kingsmill Bond, an analyst at Carbon Tracker, in a press briefing held prior to COP26. “The announced pledges of global leaders would take us to 2.1°C […] and we have to push the envelop to get to 1.5°C. That’s the context of the debate [at COP26].”

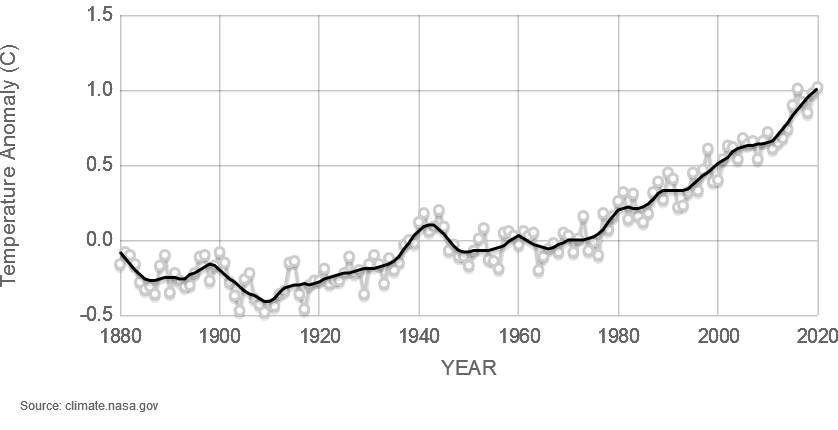

We’ve come a long way, but we have a long way to go, and time is of the essence. This was made clear in this year’s IPCC report in which the organization explained that unless drastic, immediate, and unified action is taken, our ability to limit global warming to 1.5°C — or even 2°C — will be beyond reach. The report states that carbon emissions need to be reduced by roughly 40-45% in the next few years to remain on track. However, it’s becoming apparent that these efforts are not enough to meet the Paris Agreement, and that current emission trends will lead to a warming of 3°C or more.

The effects of climate change can already been seen around the world. Rainfall was recorded for the first time in history in August on the Greenland ice sheet, which is hypothesized to be a result of record high temperatures experienced in the country that summer. Meanwhile, cherry blossoms in Korea have bloomed the earliest they ever have in over 1,200 years. The full bloom date is traditionally midway through April, but this year the cherry blossoms were announced fully bloomed on March 26.

Catastrophic climate events around the globe are also becoming more common place. In February, an avalanche in India’s Chamoli district resulted in over 270 missing or dead. Heavy snowfall followed by warming conditions caused the snow and rock avalanche as well as flash flooding shortly thereafter.

This urgency is predicted to be a headliner at this year’s COP26 conference, where world leaders will have to address how decades of inaction and a continuing slow transition to renewable energy are accelerating the frequency and severity of climate change events.

Acknowledging global inequity

Another front-runner at this year’s conference is likely to be global inequity in the face of the climate crisis. While many nations have pledged to become carbon neutral between 2030 and 2050, it is still the world’s wealthiest nations that are responsible for a majority of global carbon emissions, and there has been little progress toward collaborative, multilateral solutions to the problem.

The climate crisis and inequity are inextricably linked, where its effects will (and have) hit poorer and vulnerable communities harder. A 2017 report by the United Nation’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs defined this relationship as a viscous cycle, where initial inequality causes poorer communities to suffer more from the climate crisis, which results in further inequality. These are typically found within the Global South, and they are bearing the brunt of the Global North’s larger carbon footprint.

At the COP16 in 2010, and then re-confirmed during the Paris Agreement, developed countries promised $100 billion annually in climate finance to developing nations to help them cope with extreme weather events as well as fund projects that would help establish sustainable transportation and renewable energy. This commitment has been central to the climate accords and is an important symbol of trust, say experts, though it falls short of the estimated $1 trillion annually needed to make this a reality. Data is also showing that wealthy countries are continually falling short of the $100 billion agreement, with $79.6 billion mobilized in 2019 (up 1.6% from 2018), much of which was in the form of loans.

Acknowledging the depth of this inequality will be crucial, and likely a point of contention, at COP26.

This also ties into the feasibility of a transition toward renewable energy sources for poorer nations. Recent estimates state that in order to remain under 1.5°C of global warming, 90% of the Earth’s remaining coal and 60% of it’s oil and gas needs to stay in the ground. In a perfect world, this pivot to renewable and sustainable energy would be a widespread solution to the climate crisis, but social science experts say this estimate deeply misunderstands the disparity across the globe, which is only growing.

“It’s not just about oil and gas and local pollution, climate change is an extraordinarily inconvenient issue because it’s not about the oil and gas of today, it’s about the past,” said Sunita Nurain, the Director-General at the Centre for Science and Environment in New Delhi at a press briefing. “And this is why the question of keeping it in the ground makes it an inequitable debate. The world has burned tons of coal for its wealth, and continues [to do so] for its growth. What happens to energy access for the very poor in the world?”

Assuming everyone is on board on a local political level, countries in the richer Global North are better poised to make this shift given that they have the technology and infrastructure to do so. The Global South, however, will need the resources to move away from their reliance on fossil fuels and solve their energy disparity in new and innovative ways.

“That’s the discussion we should be having. What happens to future energy needs? Can we make sure that, instead of coal, we can supply [these countries] with other sources?” Nurain said. “We live in an interdependent world. If the rich polluted in the past, the poor will pollute in the future. We need a system that we can all live within the limit of 1.5°C.”

The shift away from nonrenewable energy sources is an important step, but it means nothing without tackling the full scope of that shift, which includes providing poorer countries with the infrastructure necessary to rely on renewable energy vs. developing through fossil energy, as the Global North once did.

How do we fund the transition?

An important aspect of climate justice is viewing climate finance within the context of a bigger shift, says Bond. He, and many experts in the field, predict that it will be cheaper to transition to “green” energy technologies than to not. “The more you deploy it, the cheaper it gets,” he said. “It’s worth spending capital today to reduce long run costs.”

Bond predicts that 2-3% of GDP is needed to be put toward investing in the energy transition. The financial benefit later on will be significantly greater.

“Politicians are a lagging indicator, the driving factor is technology, that’s what can be done at COP26 now,” he explained. “They can set concrete targets for 2030 — 2050 is too far away — and stop subsidizing fossil fuels and start to tax them. Polluters should pay for the pollution they incur.”

Bond says he is optimistic because of the collapse in cost in renewable and carbon capture technologies and advancements made in places like Denmark, Holland, and California, where governments have begun to crack the problem. “Ten, twenty years ago, when these COPs were first being designed, [these options] were of course fossil fuels and it was a real battle,” said Bond. “Looking forward, these will be renewable technologies.”

COP26 members will have to tackle the issue around who should finance the global energy transition while addressing global disparity in burning fossil fuels for economic growth. “Wealthier countries have spent almost 200 years, in some cases, burning fossil fuels, and they’re not being ask to cut without getting through the same level of development,” said Matthew Bey, Stratfor senior global analyst at RANE, in RANE’s podcast. “[The argument] is that developing nations should not have such stricter commitments or else the developed world should help pay for the divide.”

Effective response to the climate crisis continues to grow more urgent as time passes. This year, negotiators will have their work cut out for them and this article has only touched on a few of the many topics up for discussion. While there is a dire need for accelerated solutions, the next step the world takes toward fighting the crisis is hanging on the outcome of the next two weeks.

Written by: Victoria Corless and Kevin Hurler