Water is a crucial resource. It obviously keeps us alive and helps our crops grow, but the power of Earth’s oceans has the potential to offset 64% of the United States’ energy consumption if we choose to rely on it. Some geologic research also points to water as a necessary ingredient in plate tectonics, where it increases the plasticity of rocks subducting into the mantle, allowing for their deformation and melting.

But while Earth’s water is so crucial to physiology, biology, and geology, the origin of that water is a hotly debated topic.

The prevailing hypothesis

One of the more widely accepted theories of where Earth’s water came from states that the planet was “seeded” during its early life. As the Earth was accreting — the process of particles accumulating into a massive object under the force of gravity — some of the material it consumed consisted of icy planetesimals. Early Earth then further collected water through the impact of icy asteroids on its surface. However, this theory likely doesn’t tell the whole story, as discussed in a newly published study in Physical Review Letters.

“[T]his source seems to be very limited,” said co-author Artem Oganov in a press release — Oganov is also a faculty member of Skoltech’s Center for Energy Science and Technology. While some of Earth’s water could certainly be from asteroid impacts, it likely is not the reason for the planet’s endless oceans.

“The isotope composition of water in comets is quite different from that on Earth,” Oganov continued. The water in comets contains a compound called deuterium, which is a heavy hydrogen isotope. More specifically, the amount of deuterium in ‘comet water’ is up to three times the amount in Earth’s oceans.

“The consequence is that the Earth’s water must be primordial, not brought by comets,” Oganov stated in an email to ASN.

An extinct chemical: Magnesium hydrosilicate

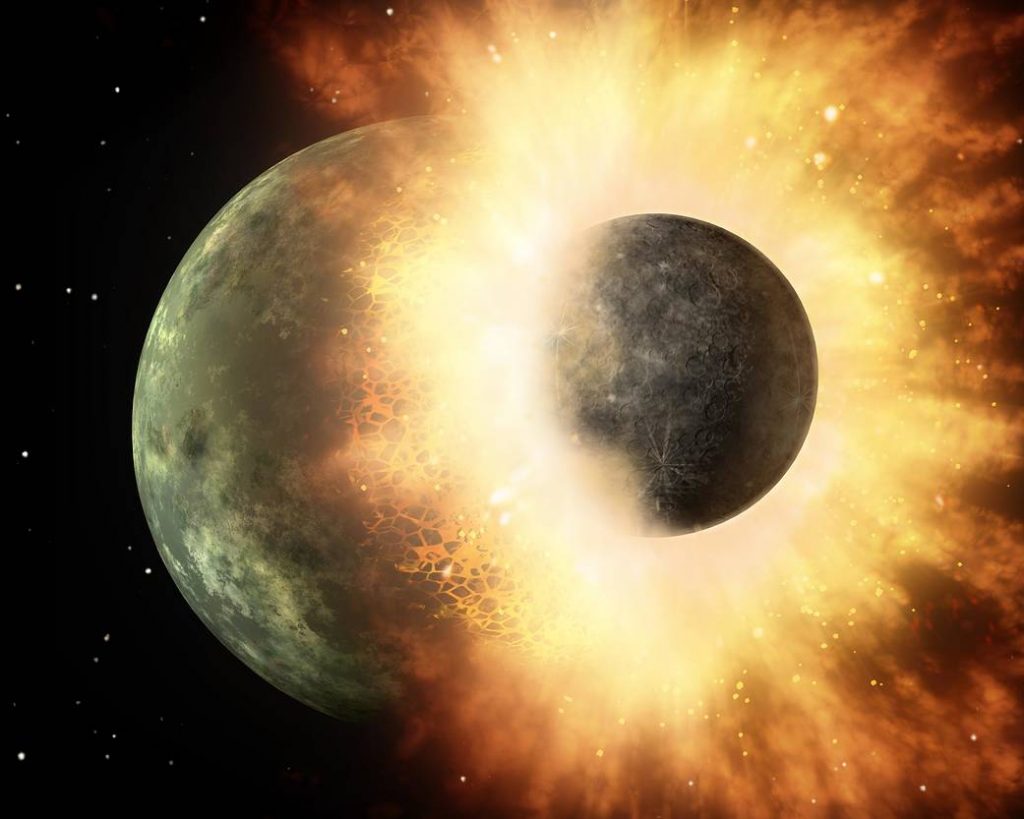

Oganov and his colleagues, led by Professor Xiao Dong of Nankai University, argue that the water came from inside the Earth, protected during the planet’s fiery infancy where it was bombarded with asteroids and Theia, a theorized planet the size of Mars.

Oganov and a group of Chinese scientists developed a methodology called “USPEX” (Universal Structural Predictor: Evolutionary Xtallography) to investigate, where they fed their code the various chemical elements that were present on Earth during its formation, as well as the pressure of Earth’s interior. Through this process, they were able to identify a chemical compound that may be behind the presence of Earth’s water: magnesium hydrosilicate.

Magnesium hydrosilicate is 11% water by weight and is stable at temperatures and pressures found in Earth’s core. During Earth’s formation, the solid core of iron that we know today did not exist yet, and magnesium hydrosilicate existed in its place. Magnesium hydrosilicate is a product of chondrites, which are meteoric rocks thought to be found in most rocky planets. “Magnesium hydrosilicate will be inevitably formed if you subject the chondrite to pressures above 200 Gigapascals,” Oganov said.

As Earth cooled and relaxed, the iron core formed at the center of the planet, which displaced the magnesium hydrosilicate to cooler temperatures closer to Earth’s surface. Here, the compound broke down, releasing its water. Over time, that water traveled to the surface of the planet, where it coalesced into the sprawling oceans we know today.

Reference: Han-Fei Li, et al., Ultrahigh-Pressure Magnesium Hydrosilicates as Reservoirs of Water in Early Earth, Physical Review Letters (2022), DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.128.035703

Quotes adapted from a press release by the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Image credit: Jong Marshes on Unsplash