Using data from the recently launched XRISM, researchers have finally resolved a long-standing puzzle about star formation in the dense cores of galaxy clusters.

“There is an old problem in galaxy clusters,” said Ming Sun, a professor of physics and astronomy at The University of Alabama, in a press release. “The core of many clusters is very bright in X-rays (meaning they should cool rapidly), so you expect over time there should be a lot of gas cooled to form stars, but you see few young stars there.”

Intense star formation is expected to occur in the cores of galaxy clusters, where intracluster gas naturally cool after radiating its thermal energy. This gas, heated to millions of degrees, emits powerful X-rays — an effect confirmed by space-based telescopes, such as NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the XMM-Newton.

However, while X-ray radiation from cluster cores has been observed, astronomers have not detected the expected levels of long-wavelength radiation from the gas that should have cooled down due to the intense radiation. Additionally, the number of newly formed stars in these regions is significantly lower than theoretical models predict. This contradiction is referred to as the “cooling flow problem.”

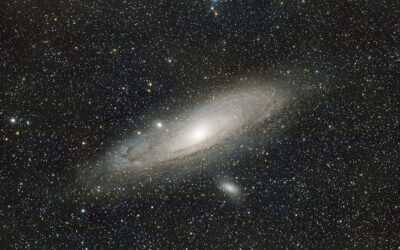

To get to the bottom of this, the research team studied the gas in one of the nearest clusters to Earth and discovered that a unique factor is at play that is preventing the necessary cooling.

A star formation paradox

To explain the “cooling flow problem” paradox, theorists have proposed several solutions in the past. The most straightforward idea is that the gas is never allowed to cool and is instead reheated by active galactic nuclei — extremely energetic regions surrounding supermassive black holes. Matter falling toward these black holes moves at extreme velocities, sometimes approaching the speed of light, and transfers energy to the surrounding intracluster gas through high-speed jets and intense radiation, slowing its cooling process.

However, this theory falls short as even in clusters where the central black hole is relatively inactive, star formation remains surprisingly low, suggesting that additional mechanisms must be preventing the gas from cooling efficiently.

Other hypotheses suggest that large-scale gas motions play a critical role. One possibility is that the gas might actually be sloshing around, triggered by large-scale events such as galaxy mergers or collisions within the cluster. This movement could prevent cooled gas from settling in one location where it could condense into stars.

Another idea is that chaotic turbulence redistributes heat, disrupting the cooling process. In this scenario, swirling eddies mix hot and cold gas, maintaining higher temperatures than expected. Such turbulent motion could arise from various sources, including the influence of the central black hole, persistent thermal inhomogeneities, or even cosmic ray pressure.

Despite their theoretical appeal, these ideas remained difficult to confirm. The resolution of earlier-generation X-ray telescopes, including Chandra and XMM-Newton, was not sufficient to directly measure the motion of intracluster gas with the precision needed to test these hypotheses.

Resolving the paradox with XRISM

The recent launch of X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission (XRISM), a space telescope developed jointly by NASA, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, and the European Space Agency (ESA), provided astronomers with an unprecedented opportunity to study the dynamics of cluster gas in greater detail.

“The key breakthrough came through a new instrument on XRISM called Resolve that provides high-resolution X-ray spectroscopy to reveal the bulk motion of the hot gas, which was completely unknown before, as well as the turbulent motion of the hot gas,” Sun said.

To investigate the cooling flow problem, the research team focused on the Centaurus cluster, a massive assembly of galaxies located about 170 million light years away from Earth. This particular cluster was ideal for the study because its central black hole is not especially active, making it possible to isolate the effects of gas motion without the overpowering influence of extreme

By analyzing XRISM’s high-resolution data alongside earlier observations from the Chandra X-ray Observatory and the ground-based Very Large Telescope, the team mapped the motion of gas within the cluster core. They did this by measuring subtle shifts in the wavelengths of X-ray emissions — a technique similar to how astronomers use redshift and blueshift to determine the motion of galaxies.

The results confirmed what theorists had suspected: The gas within the cluster core is not static; instead, it is engaged in large-scale “sloshing” at speeds of around one hundred kilometers per second. In addition, turbulent eddies were observed, further stirring the gas and redistributing heat. The combination of these effects prevents the gas from cooling enough to form stars.

Interestingly, the study found that while the central black hole does contribute to the turbulence, the sloshing motion plays the dominant role in keeping the gas warm. The researchers suggest that this large-scale movement was triggered by past collisions between smaller galaxy subclusters, which set the gas in motion and have continued to shape its behavior ever since.

Implications for galaxy evolution and cosmology

Beyond solving the cooling flow problem, these findings have broader implications for astrophysics and cosmology. The discovery that large-scale gas motion plays a critical role in maintaining the thermal balance of galaxy clusters suggests that similar mechanisms could be at work in other cosmic environments. This insight will likely lead to refinements in models of galaxy evolution, helping astronomers better understand how clusters evolve over billions of years.

The study also sheds light on the role of active galactic nuclei in regulating gas cooling. Previously, these central black holes were thought to be the primary heat source preventing star formation in cluster cores. However, the new results indicate that external factors — such as bulk gas motion — can significantly influence their impact.

This realization will be important for future research into the complex interactions between galaxies and their environments.

Reference: XRISM collaboration, The bulk motion of gas in the core of the Centaurus galaxy cluster, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08561-z

Feature image credit: WikiImages on Pixabay